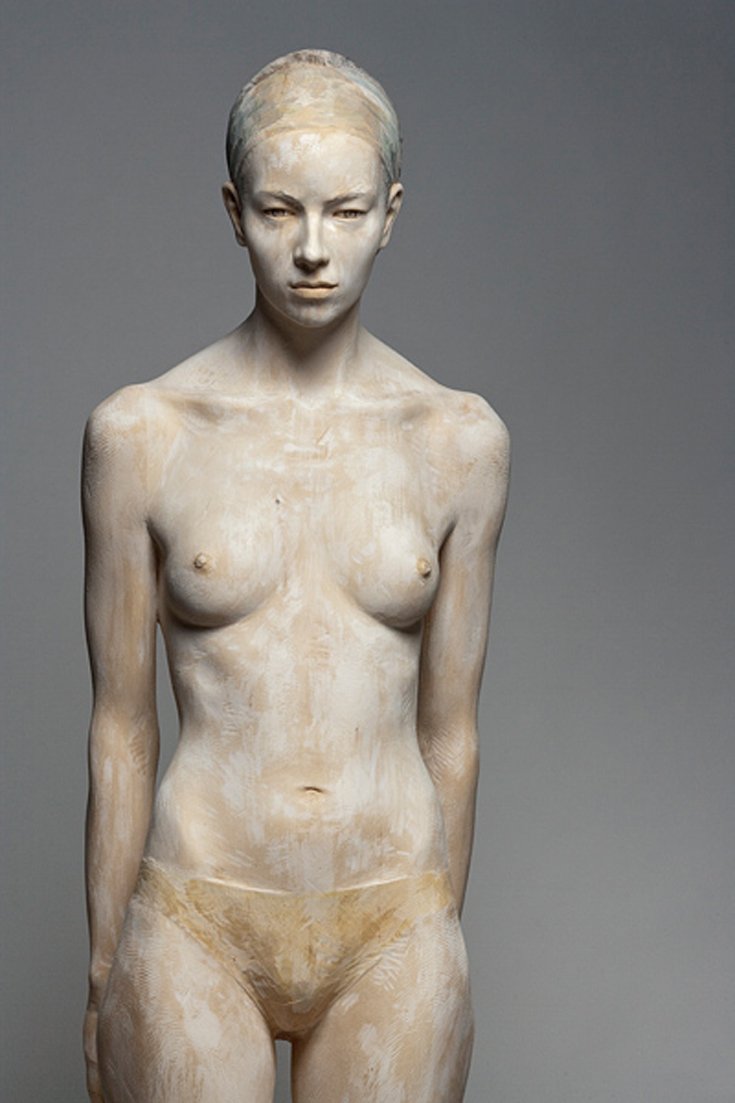

A native of Brixen, south Tyrol, Bruno Walpoth embraces the centuries old woodcarving tradition of the Val Gardena, a valley in the Dolomites which achieved fame due to the exquisite wooden statues and altars in demand all over the Catholic world, even for the peg wooden dolls, the local craftsmen produced.

Walpoth grew up absorbing the woodcarving tradition of his birthplace, a number of family members being master artisans. Like many craftsmen before him, and started a customary lengthy apprenticeship at the age of 14, in St. Ulrich, the heart of the valley’s woodcarving activity where he stayed for 5 years learning.

A shift was observed in Val Gardena’s tradition after the second World War, when the valley’s progeny started to explore sculpture academically, enriching the long-established apprenticeship system, bringing a plethora new elements into the woodcarving tradition of the area, forming a new visual language. Sailing along the wave, Walpoth pursued academic studies in Munich’s Akademie der bildenden Kuenste for 6 more years, a period that shaped him as an artist.

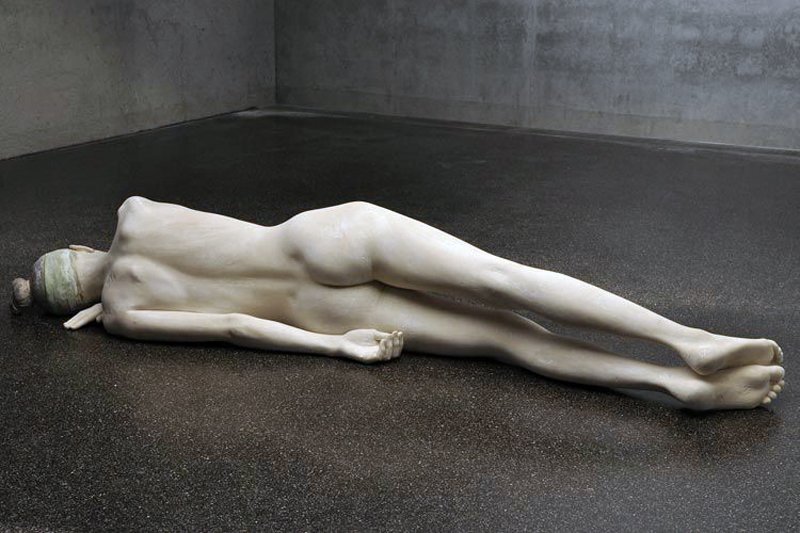

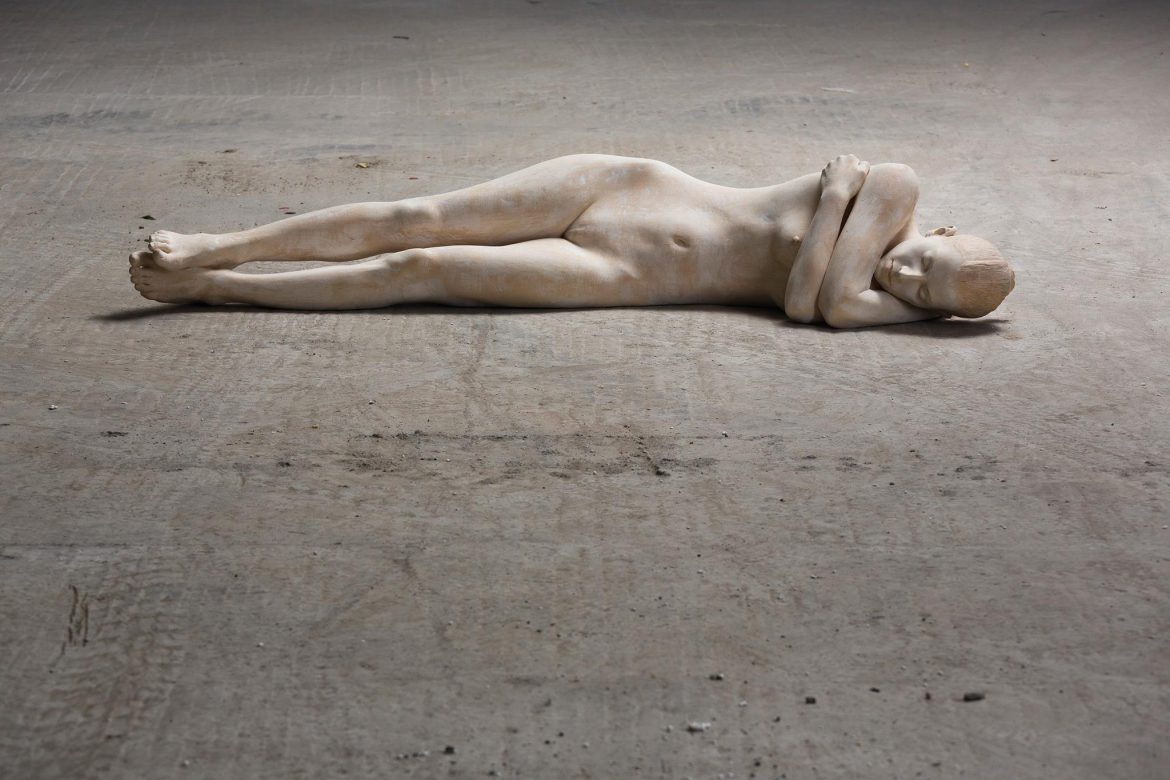

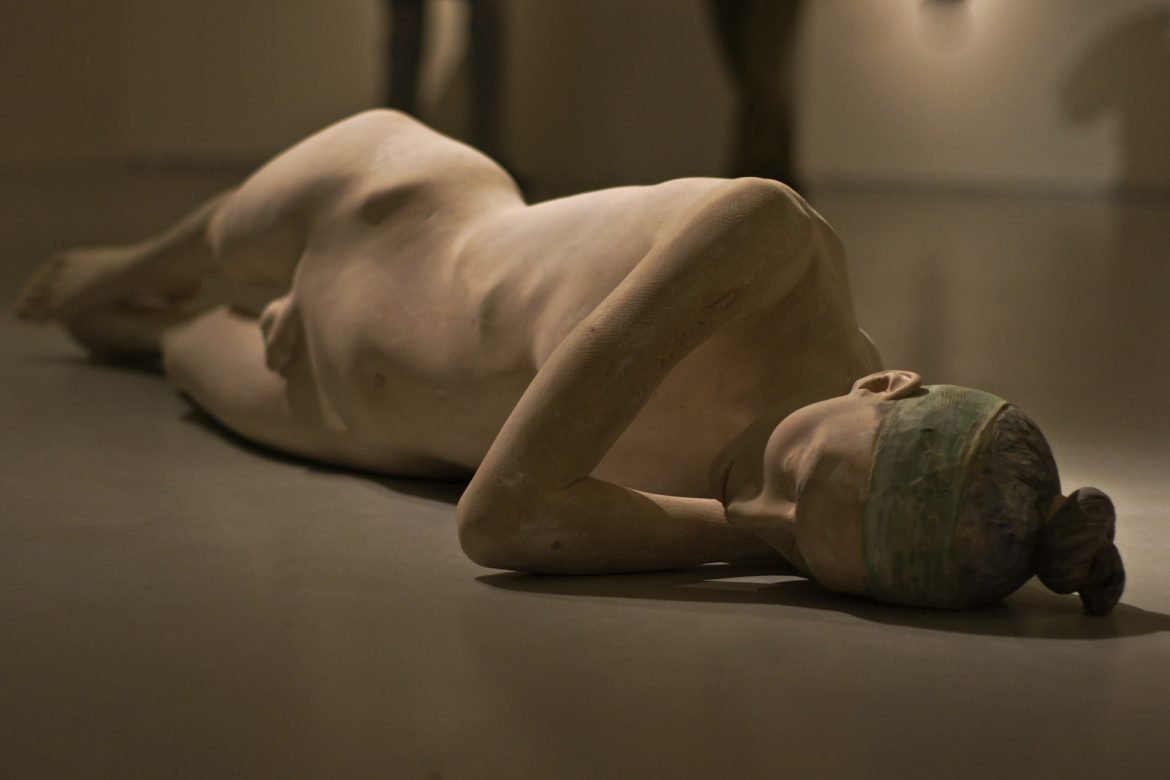

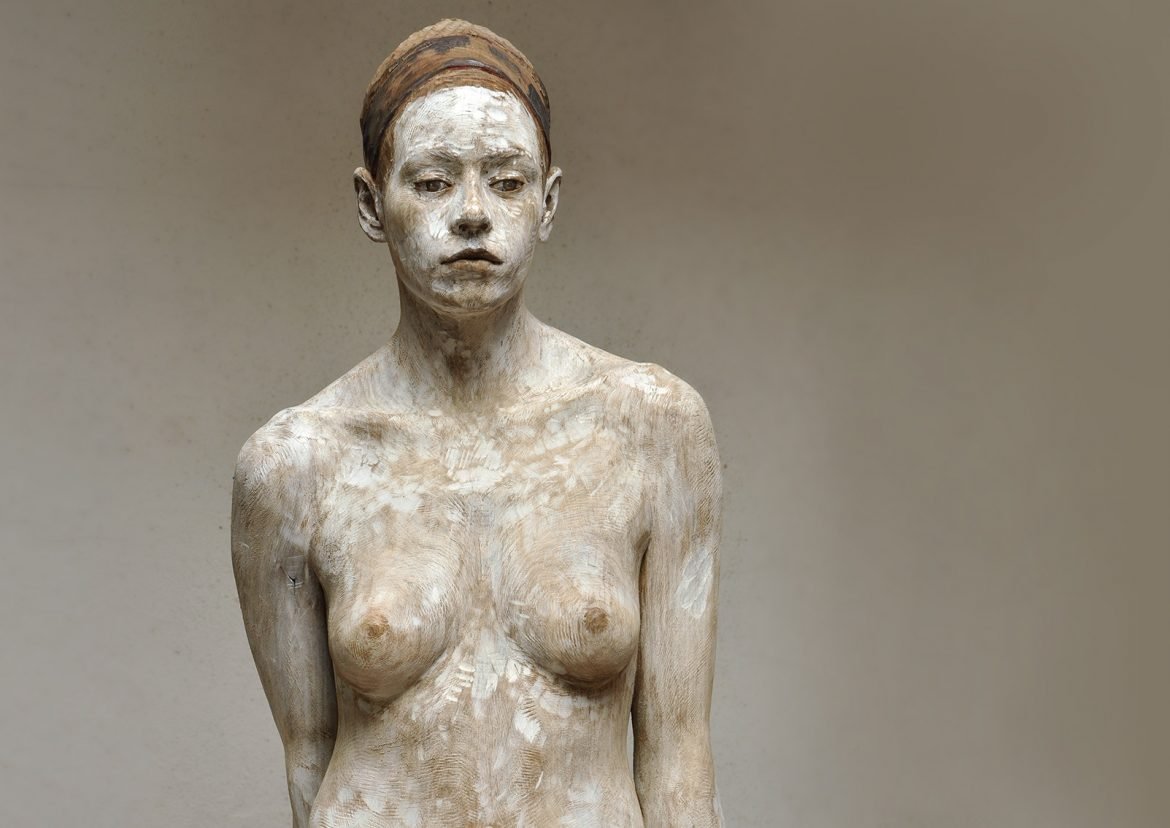

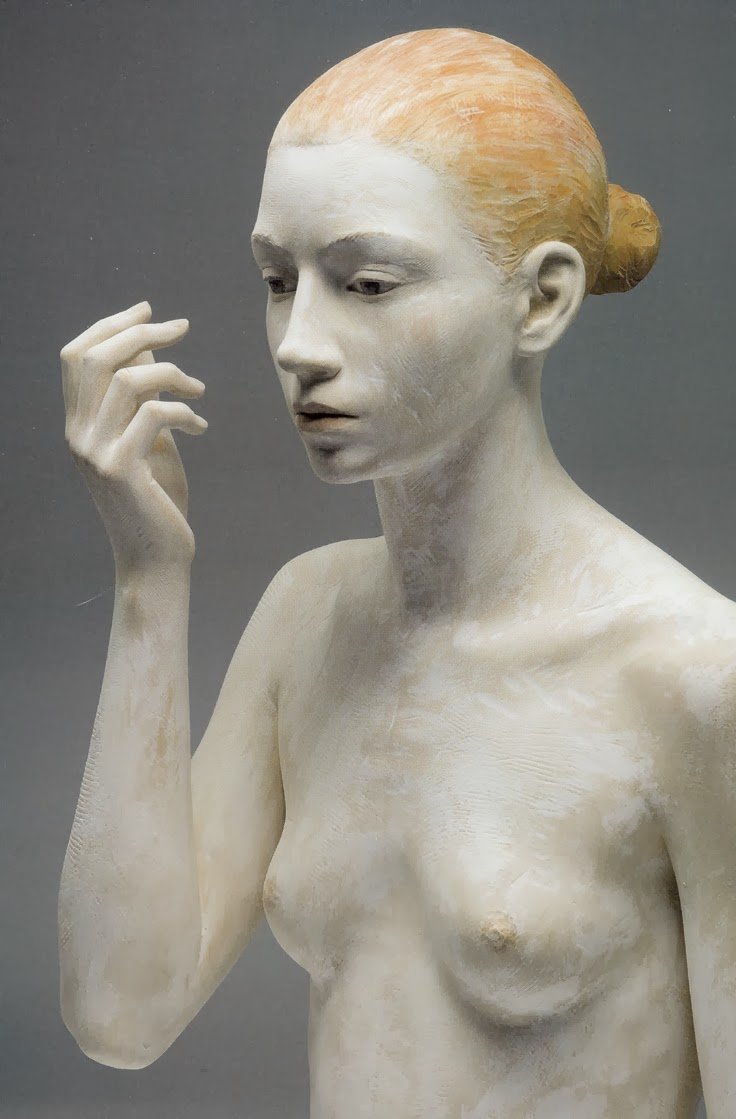

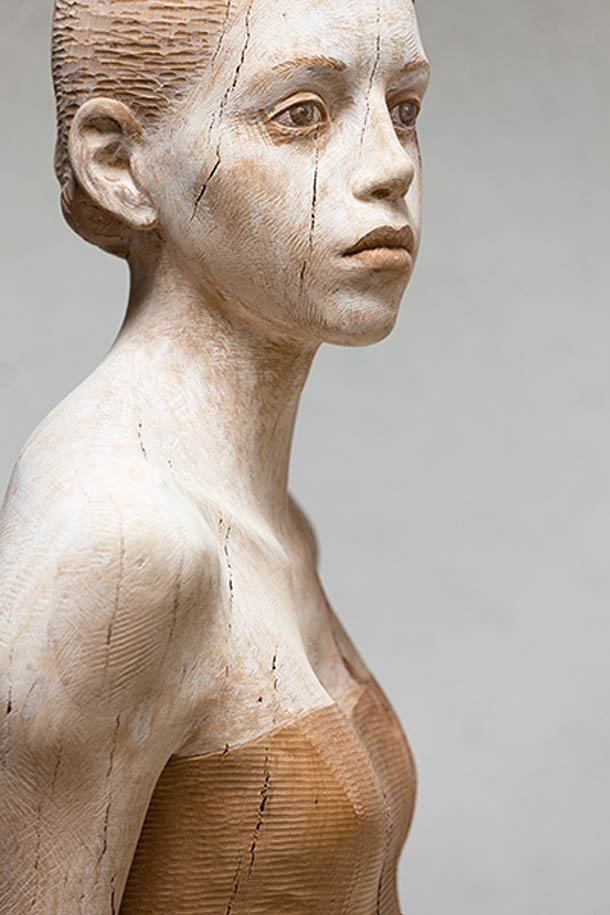

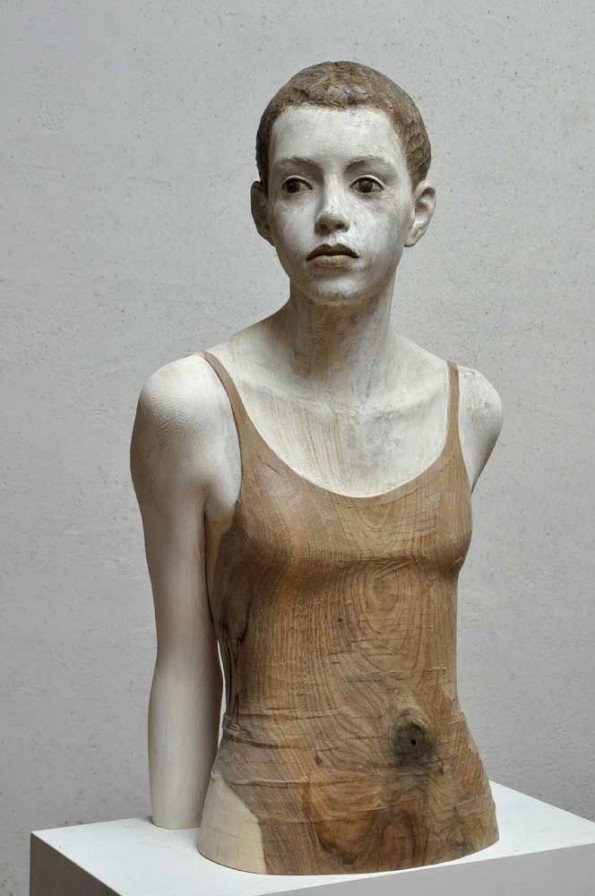

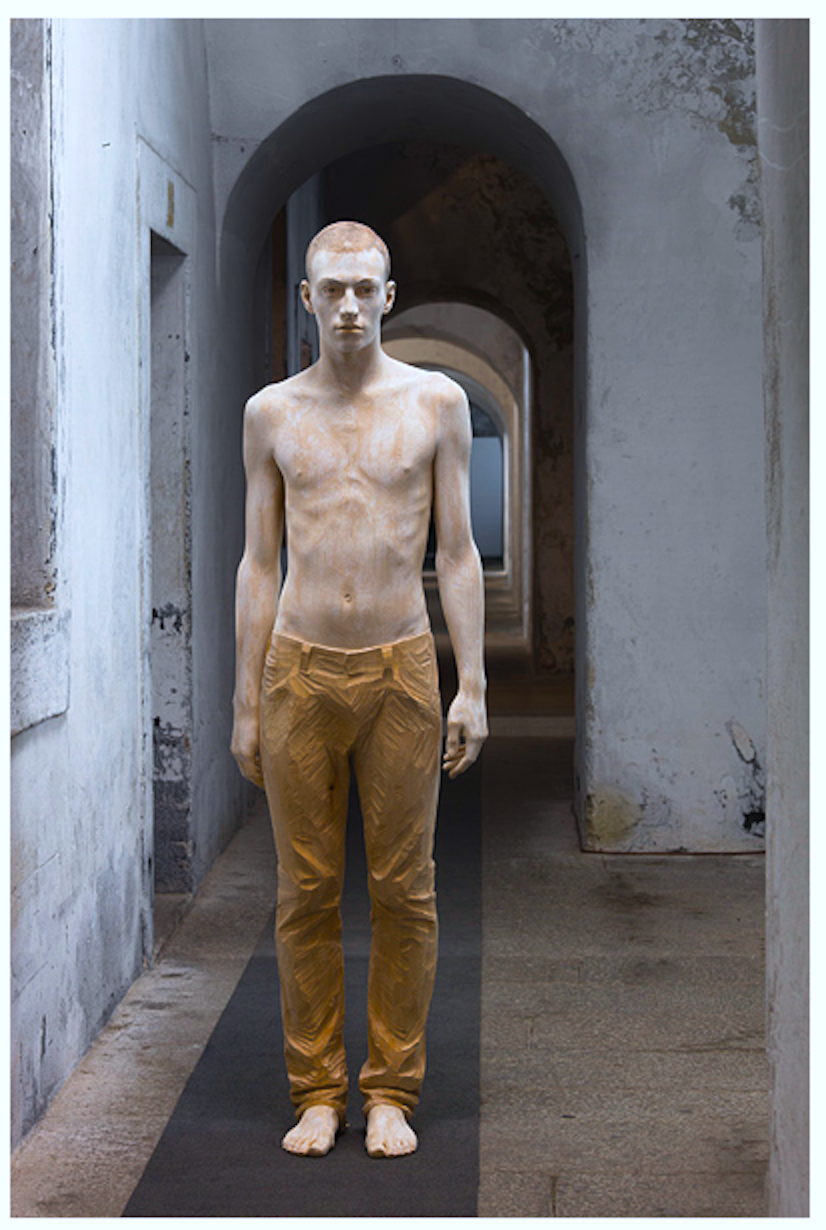

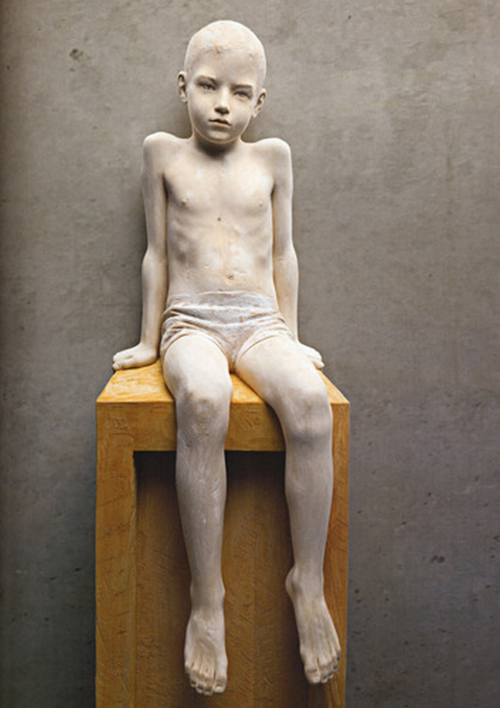

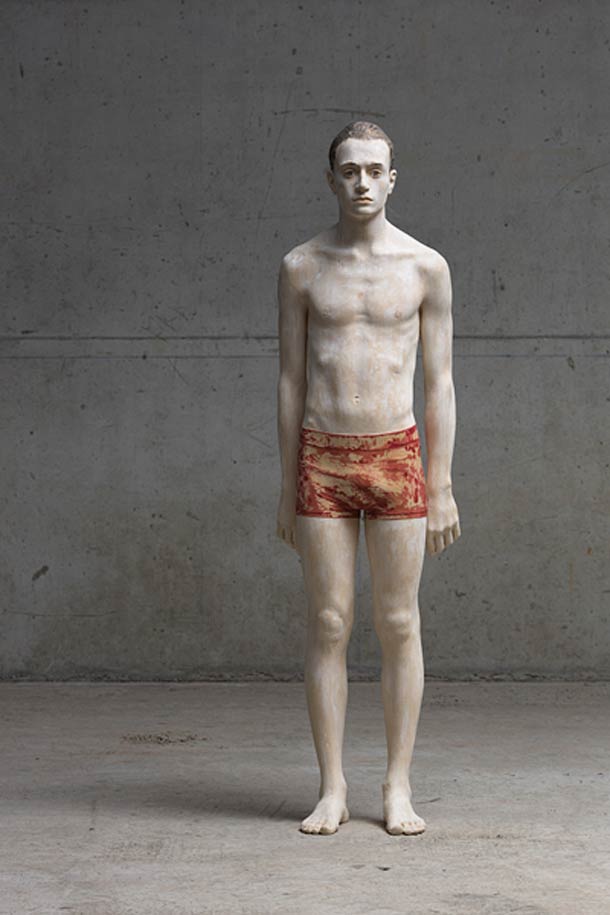

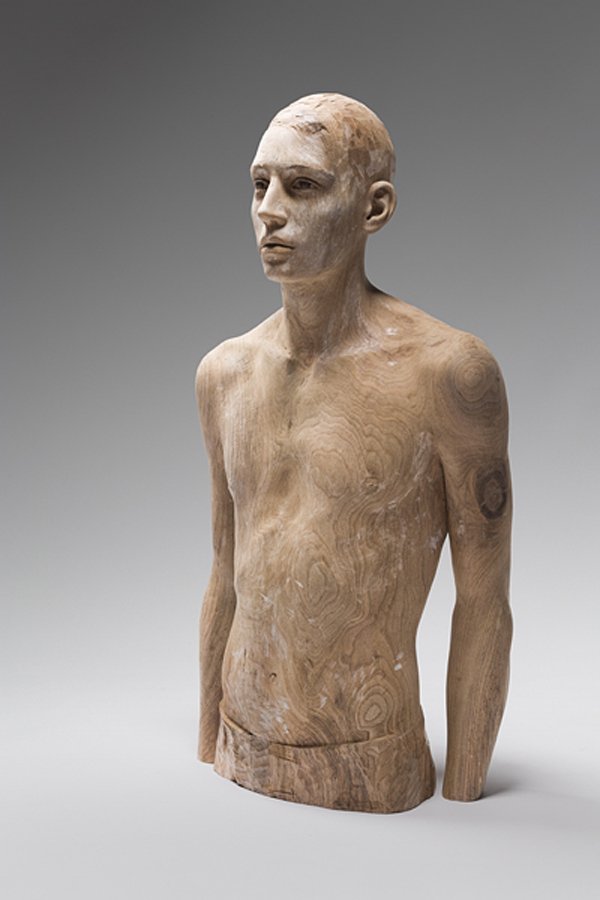

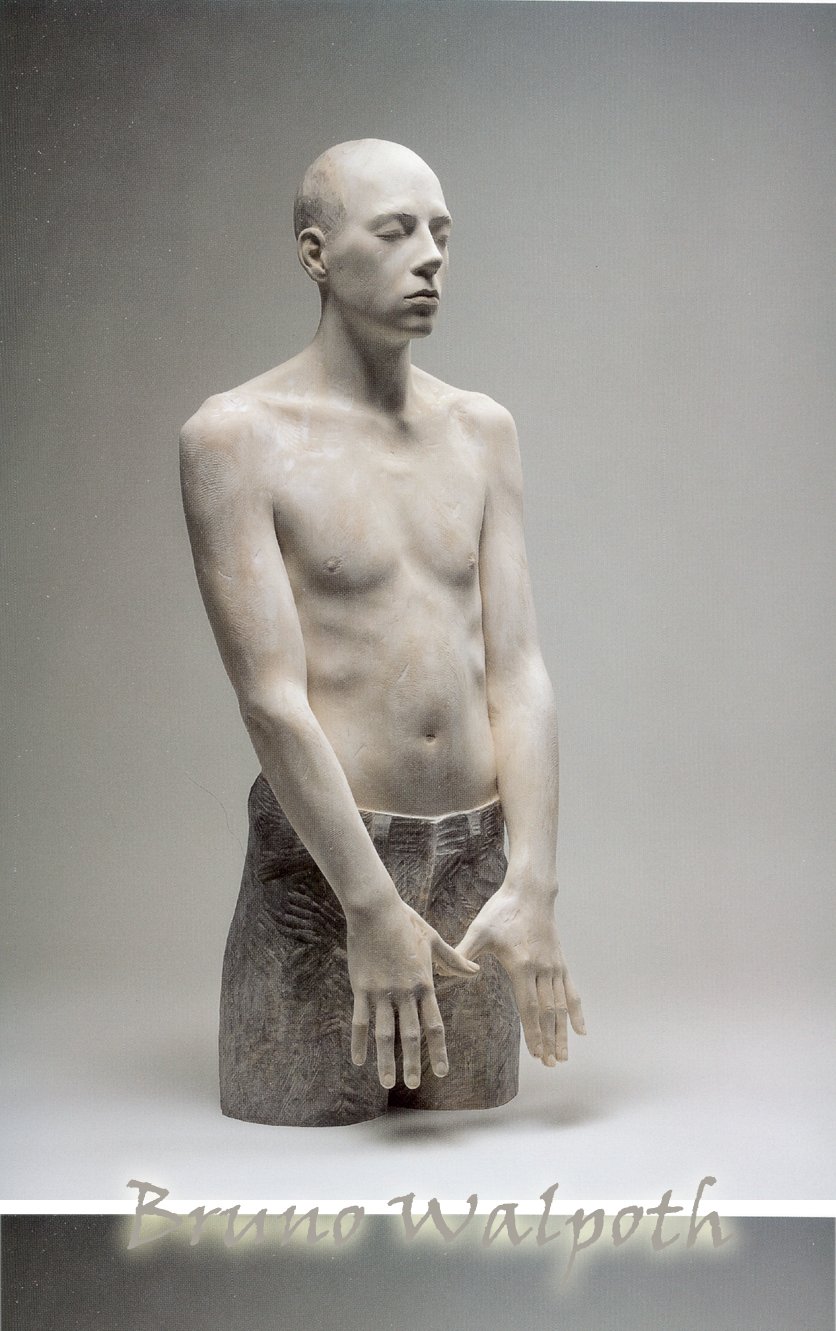

The marriage of practical experience and theoretical knowledge is evident in Bruno Walpoth’s work. Distancing himself from the religious woodcarving tradition of his homeland, he treads upon a new path, breathing life into matter; wood in his hands transcends the confines of the inanimate, it becomes alive and the viewer, like a modern Pygmalion, becomes entranced by the warmth and intimacy wood.

The prominent veneration of marble statues, god-like figures of a radiant and pure white, colour contrast obliterated, is engrained in western culture leaving wood associated by many with crafts and crude folk art; a humble material compared to the luxury marble offers. That the ancients sculptors painted statues in a life-like manner, is now a well known fact. The clash, however, of scientific findings with this established perception of centuries leaves many confused and with a mixed taste, not quite sure whether they prefer the original vivid form (as presented by museums and researchers) or the state the statues are in today, colourless images of humans turned to stone.

Yet, Bruno Walpoth’s work proves how strong the spell is; his statues are not objects, rather almost animate creations with souls, their feelings bare for the viewer to see.

Unknown to many, including the Renaissance masters and the ones that followed, is that the ancients valued marble the least of all the materials they used. Indeed, chryselephantine ranked first, the contrasting gold and carved ivory over a wooden frame, being the most precious type of statues; its material perishable. Bronze followed and marble came last. The reason so many marble statues remain is that chryselephantine ones were destroyed to reclaim the gold. Bronze statues shared the same luck. What is more, most copies of bronze statues were rendered in marble, not bronze, therefore it is pure coincidence that bronze statues have survived millennia. Marble escaped this fate, purely because it was not that useful in this regard.

The intimacy that permeates Bruno Walpoth’s statues shows us how organic, how warm wood can be, a window to the past.