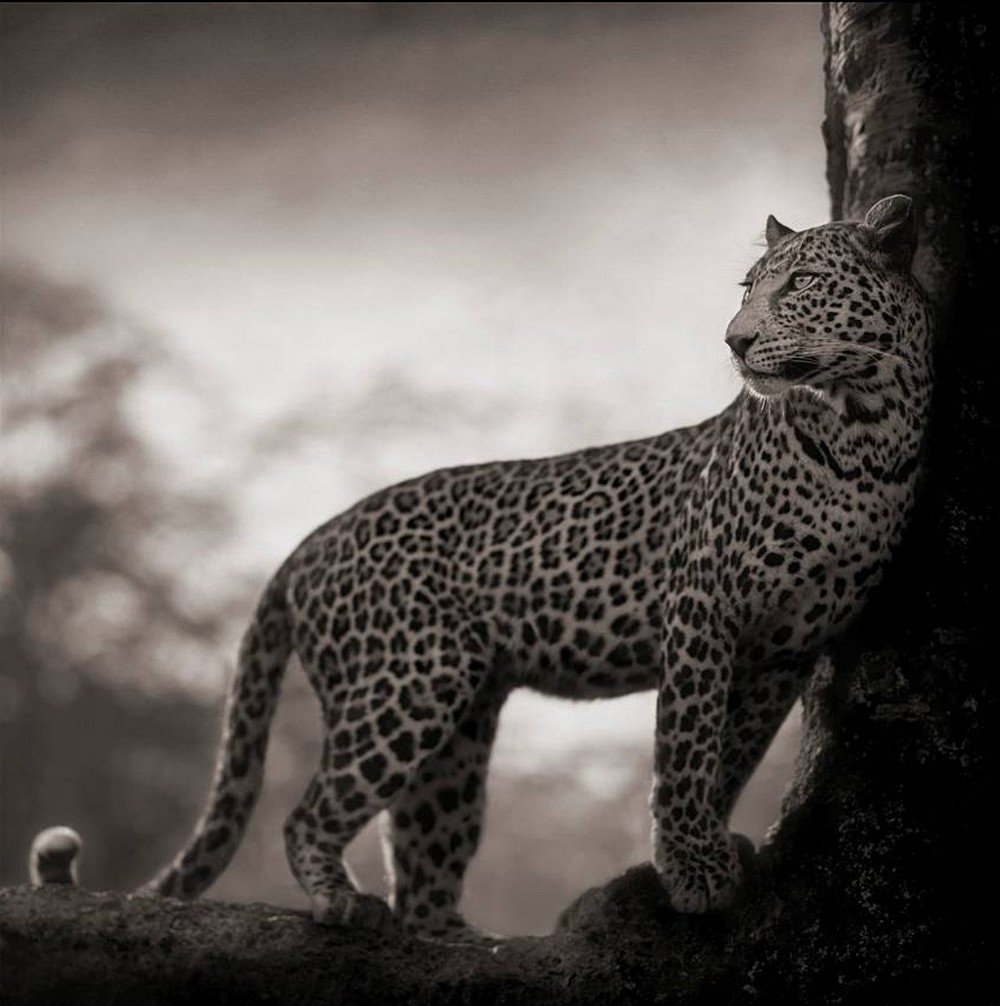

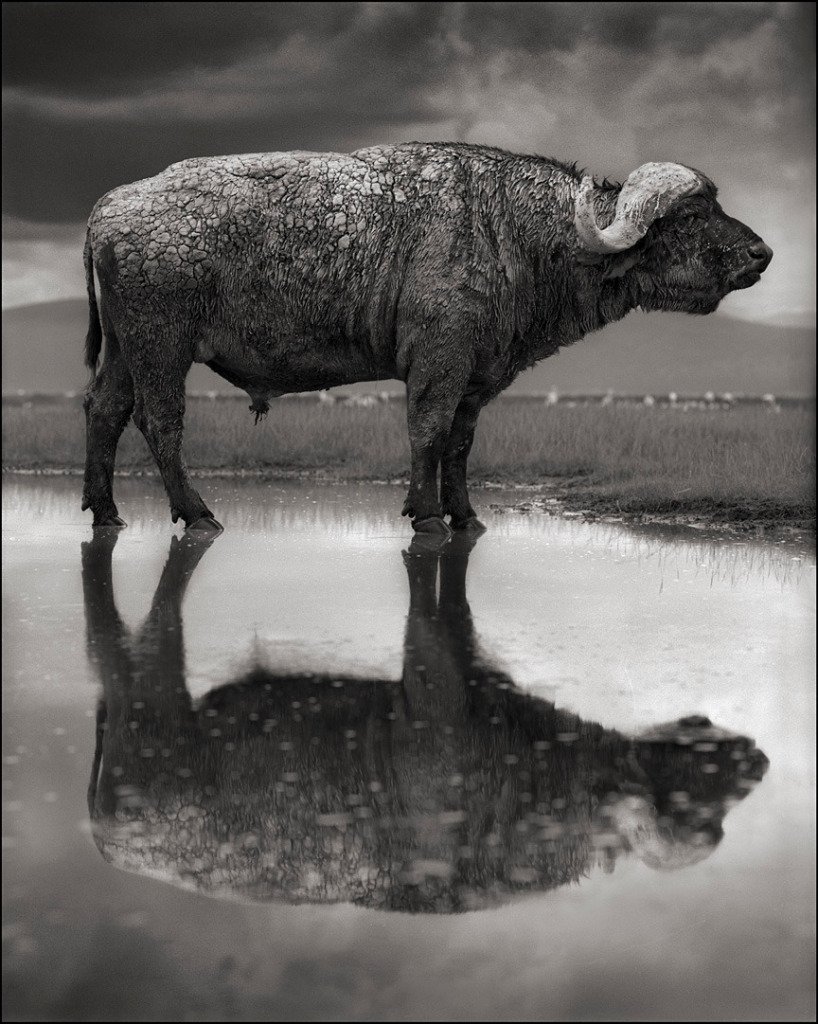

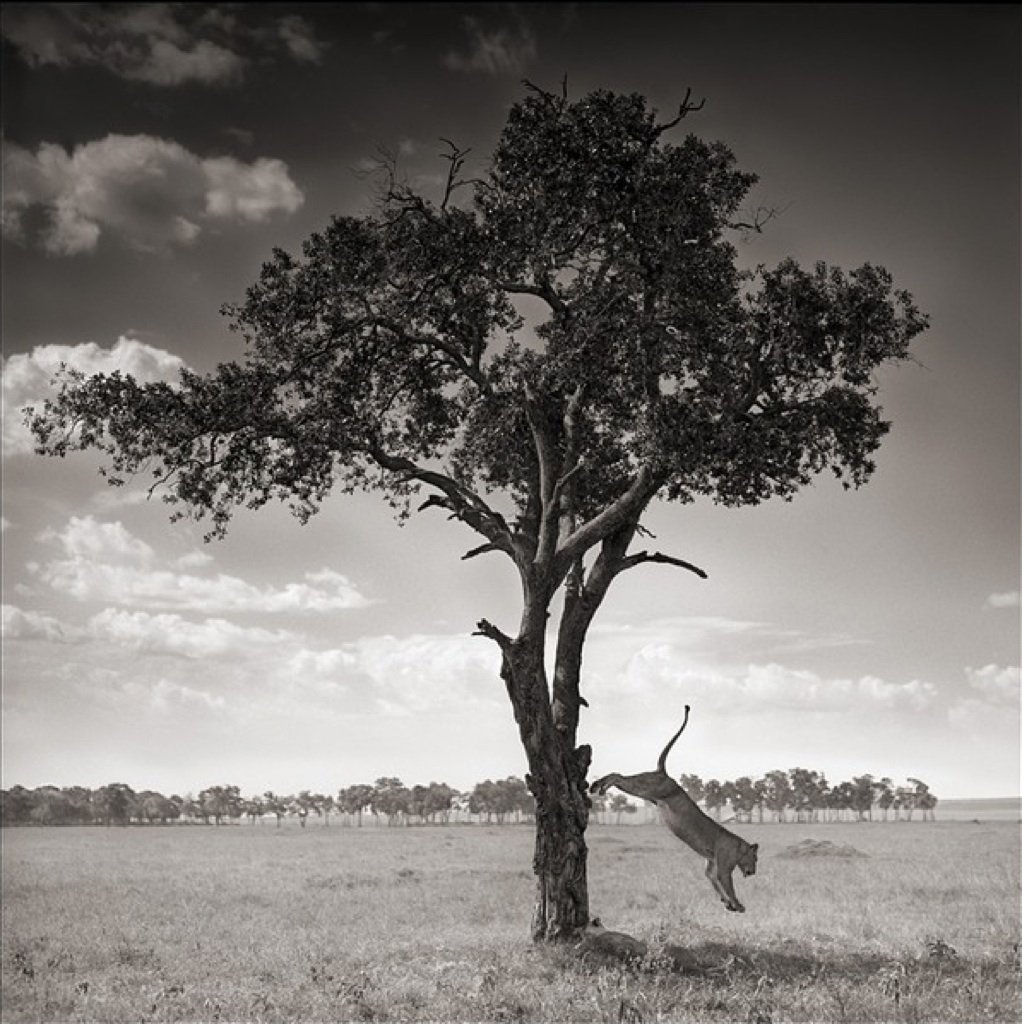

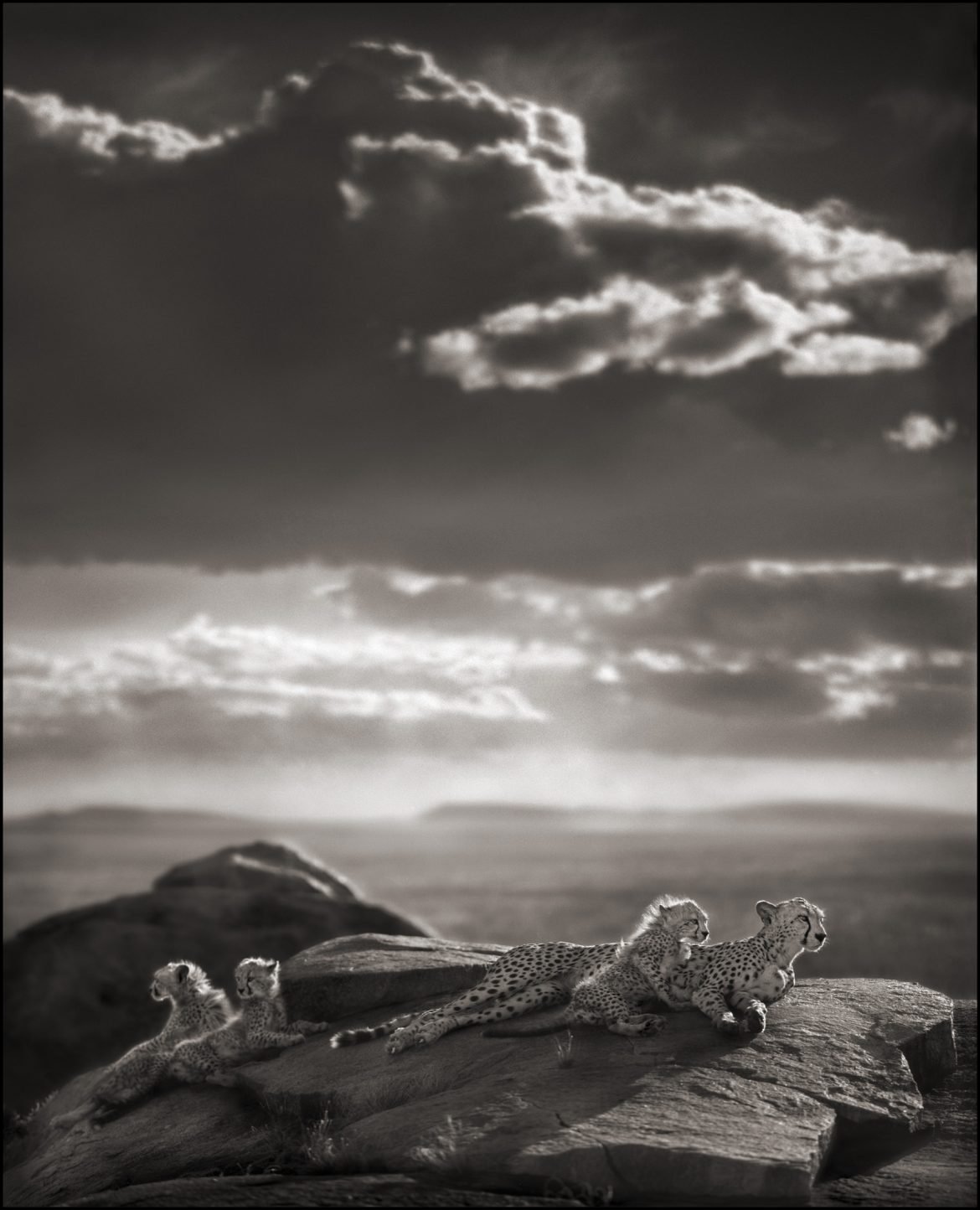

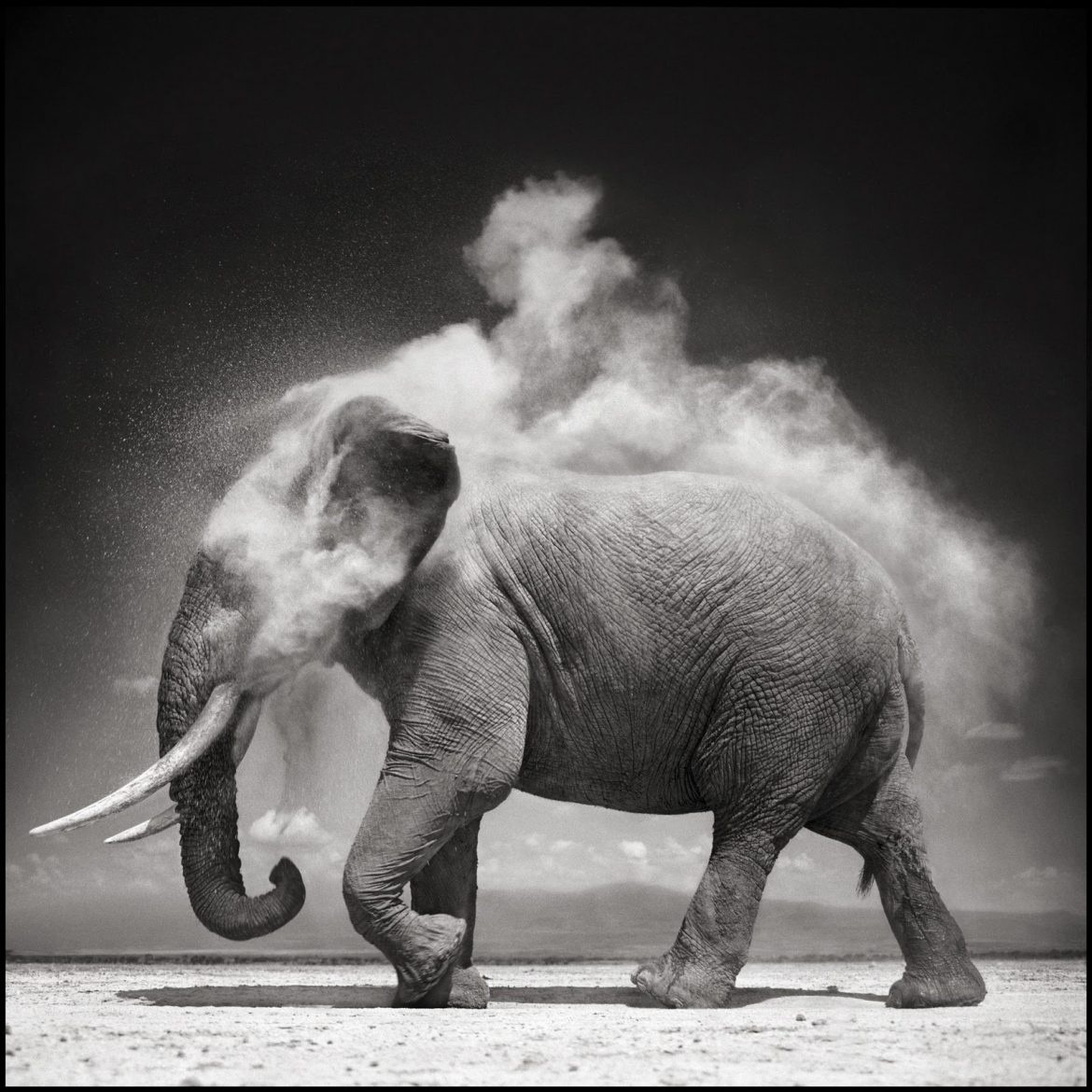

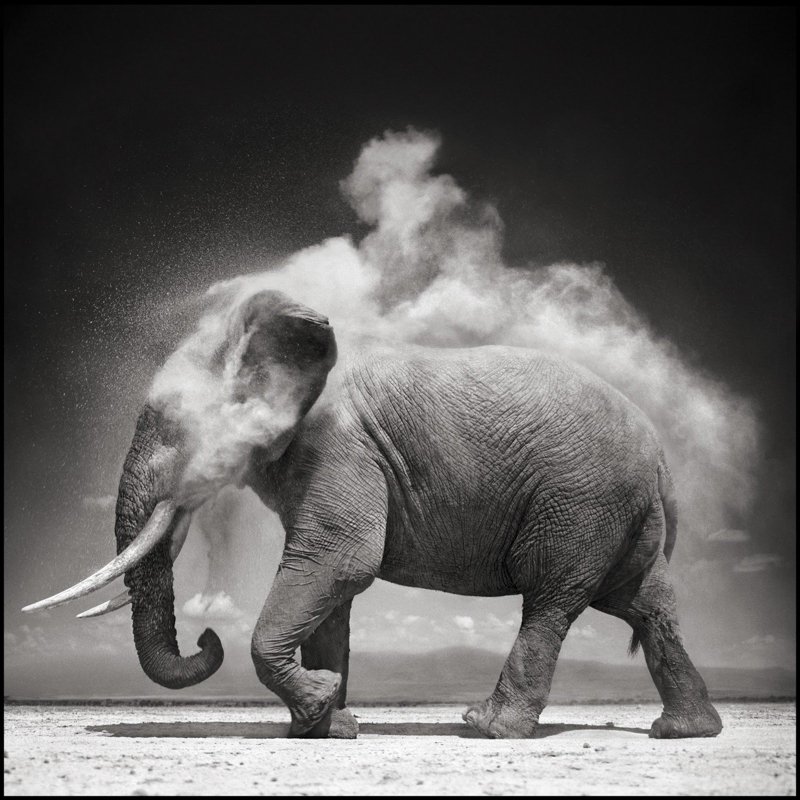

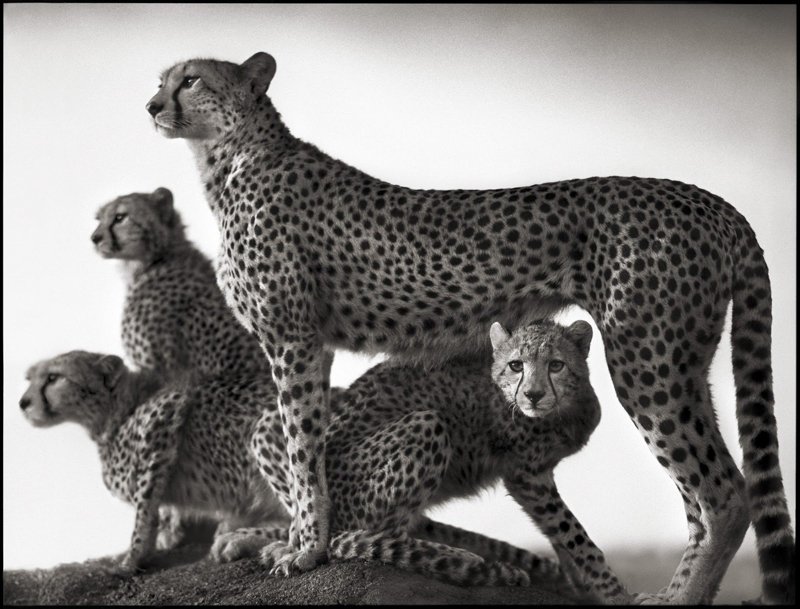

“This world is under terrible threat, all of it caused by us. To me, every creature, human or nonhuman, has an equal right to live, and this feeling, this belief that every animal and I are equal, affects me every time I frame an animal in my camera. The photos are my elegy to these beautiful creatures, to this wrenchingly beautiful world that is steadily, tragically vanishing before our eyes.” – Nick Brandt.

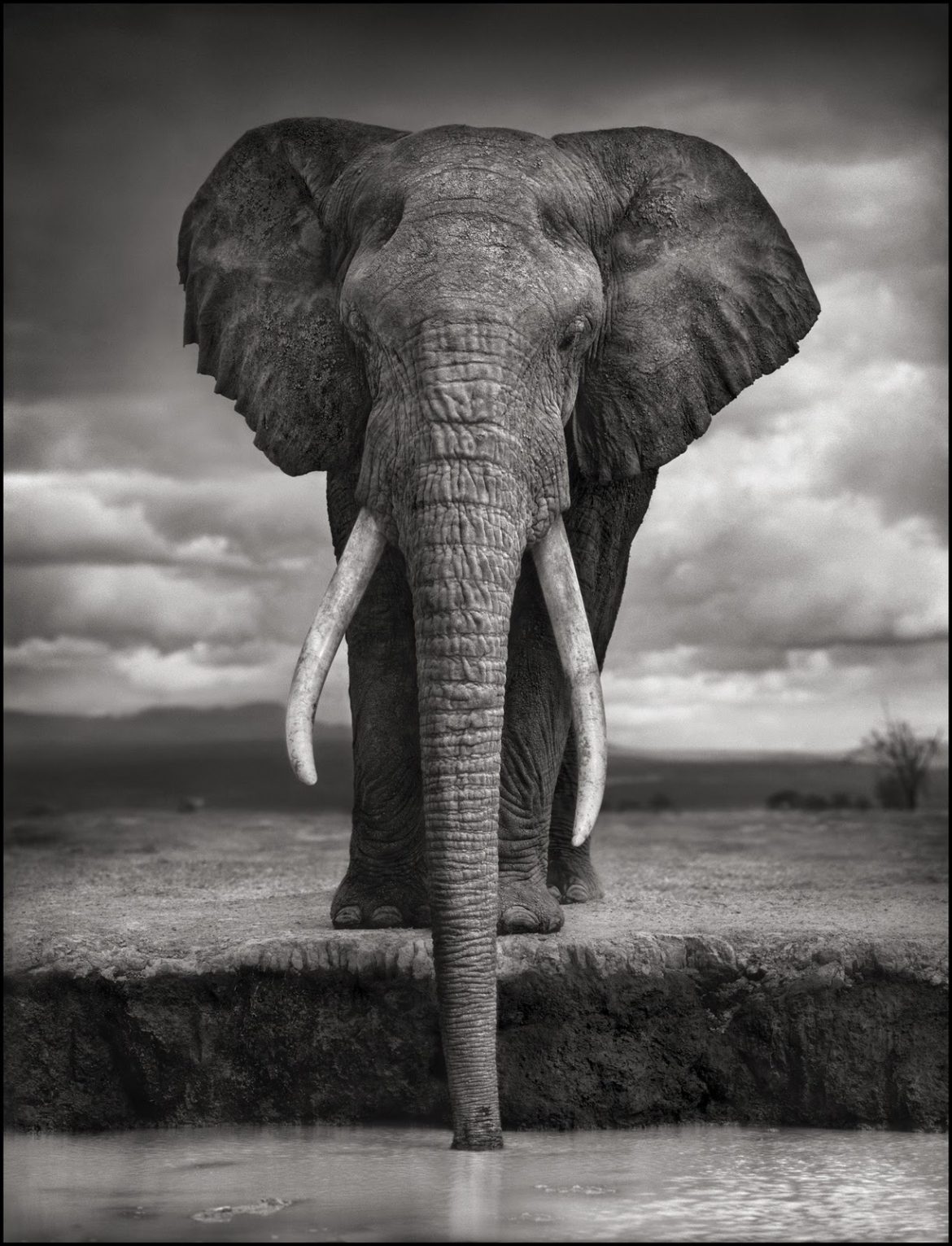

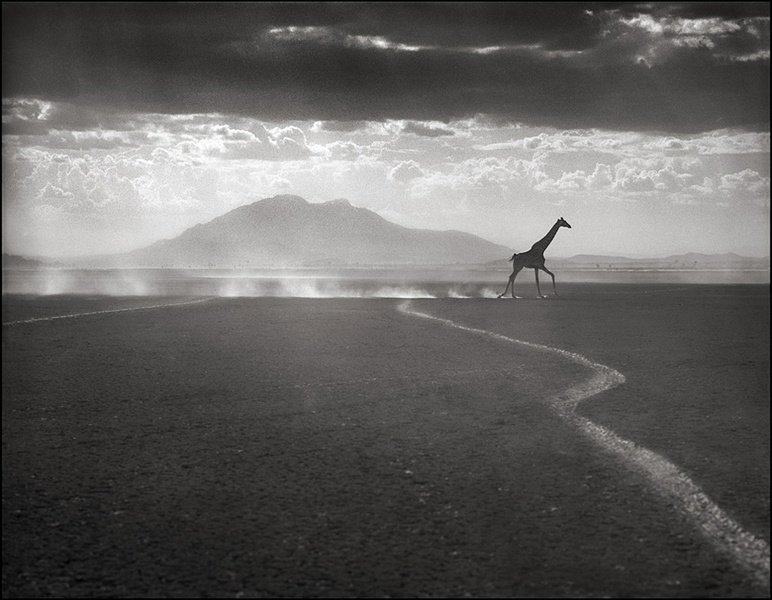

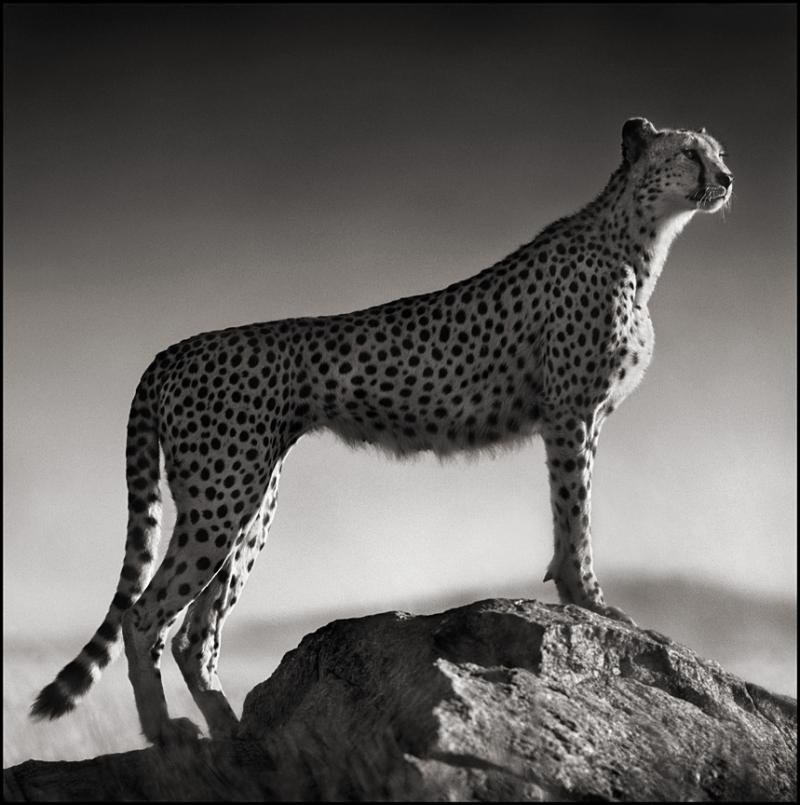

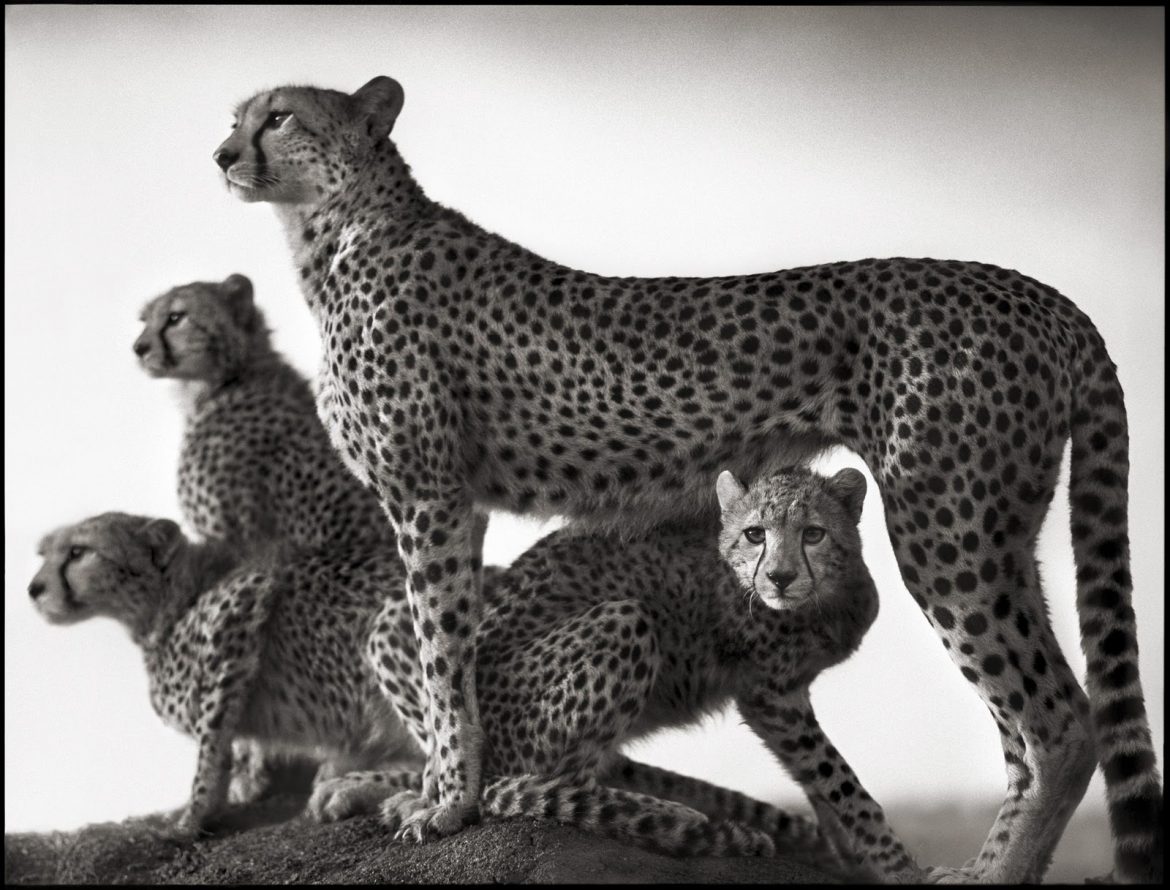

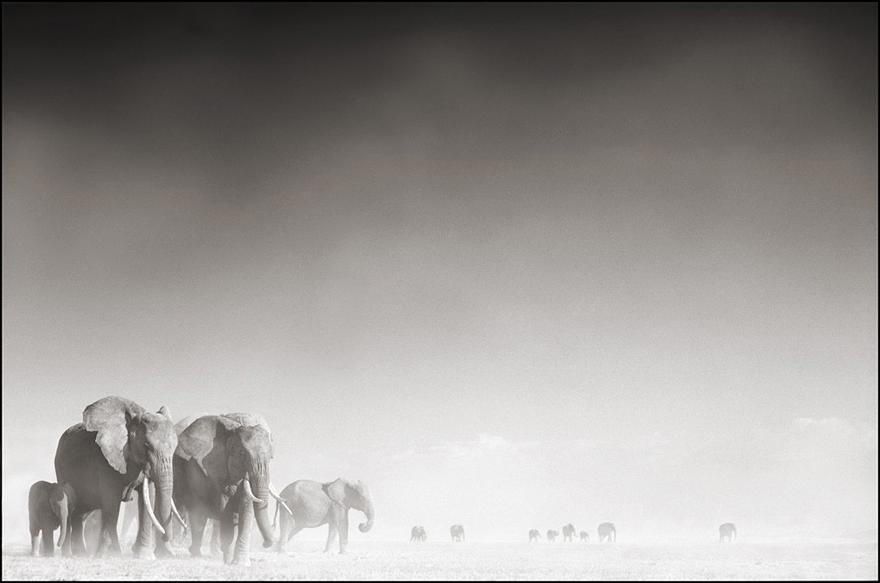

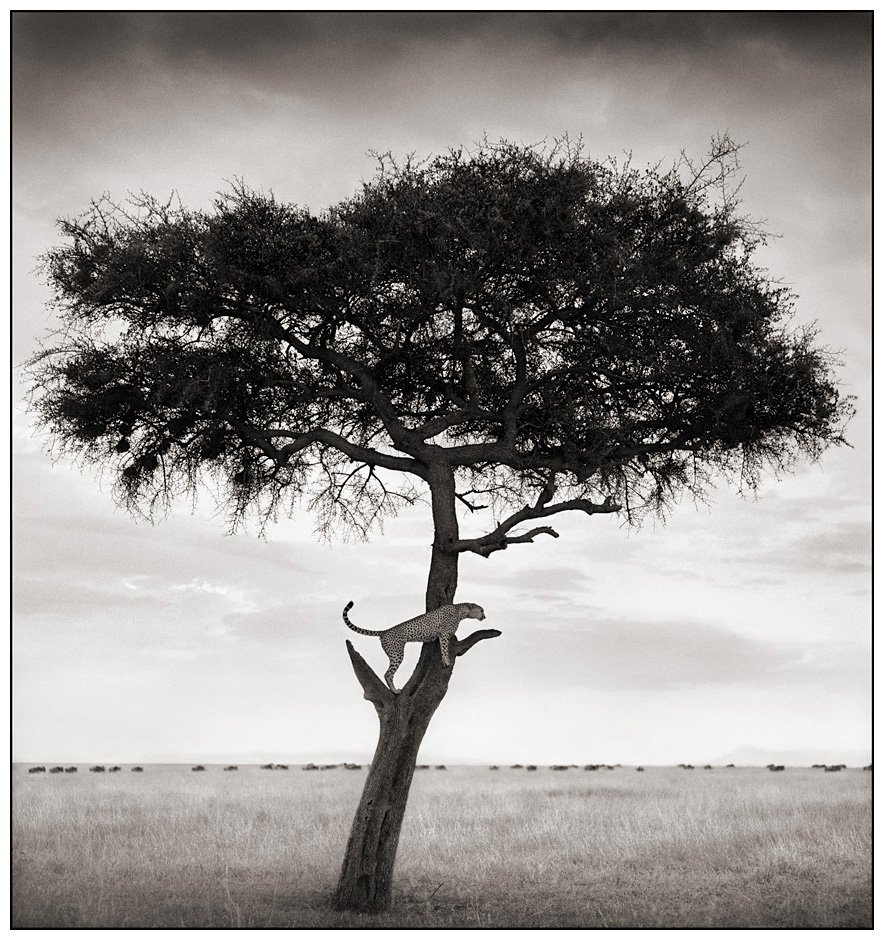

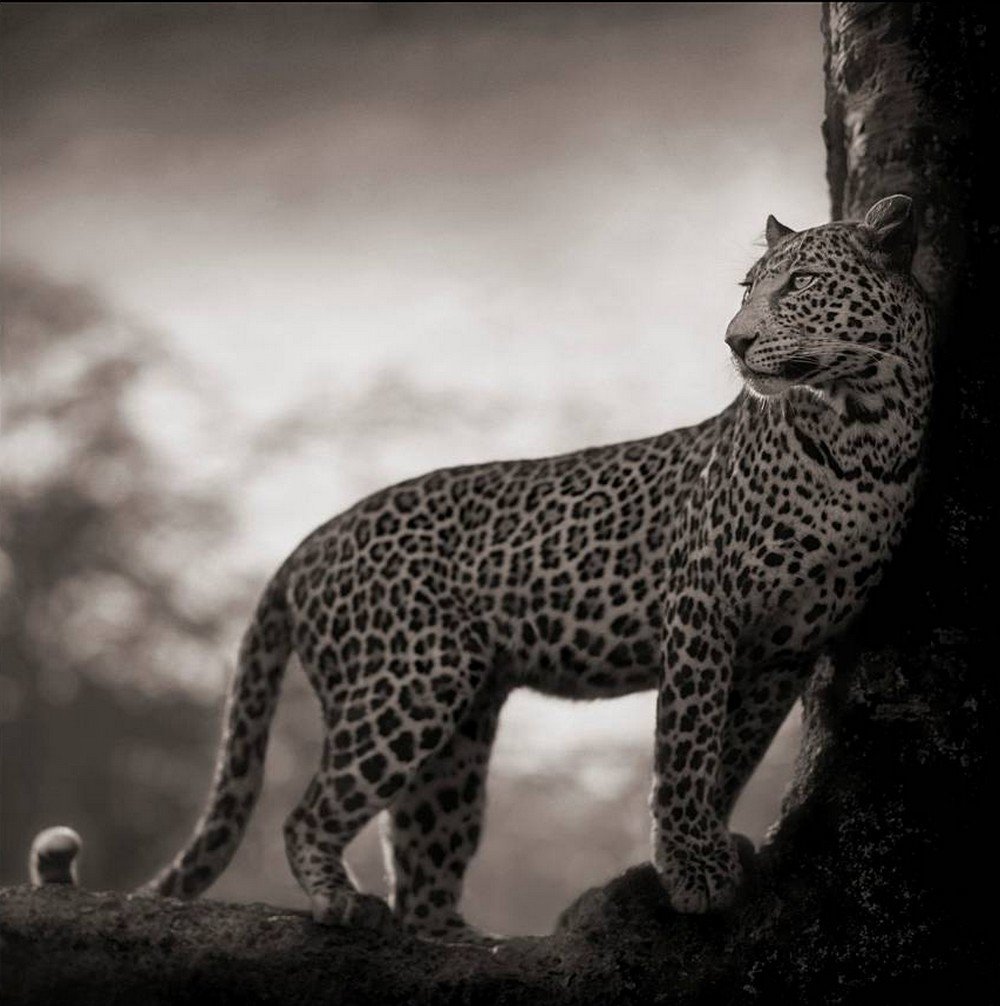

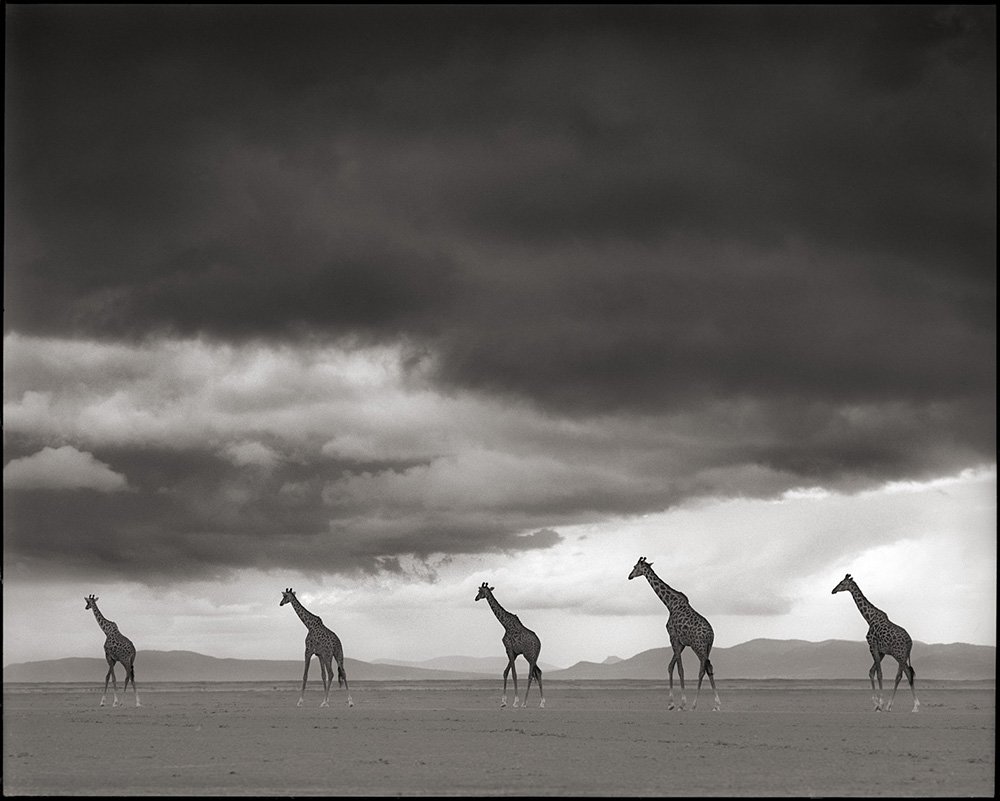

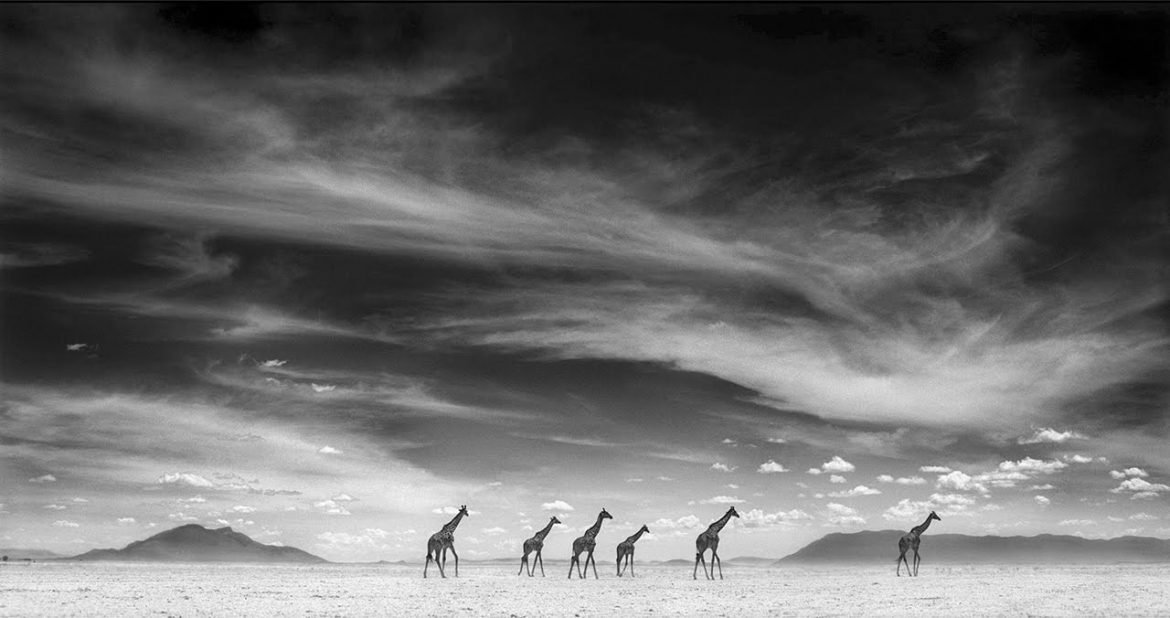

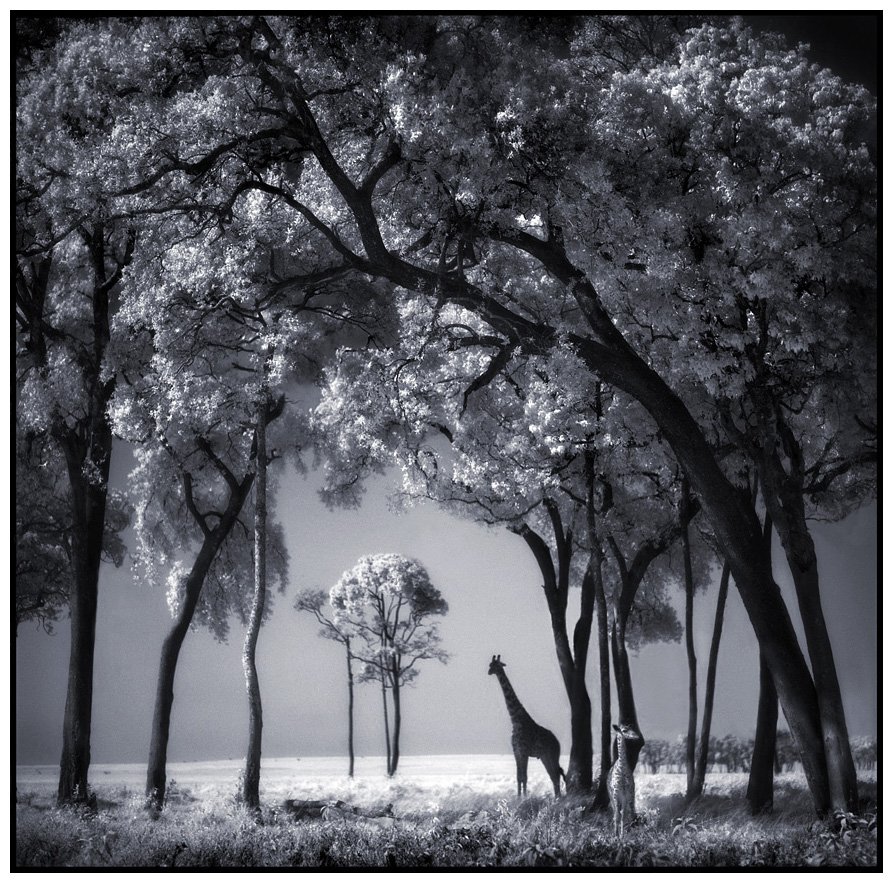

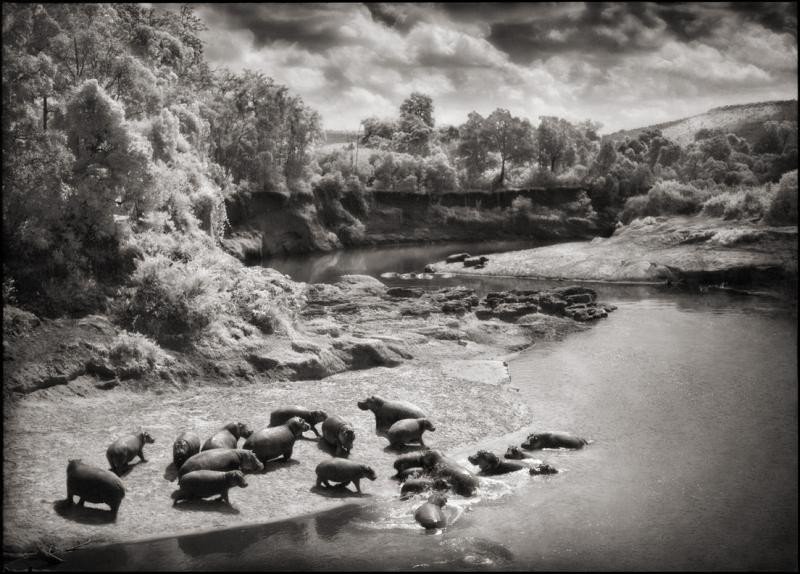

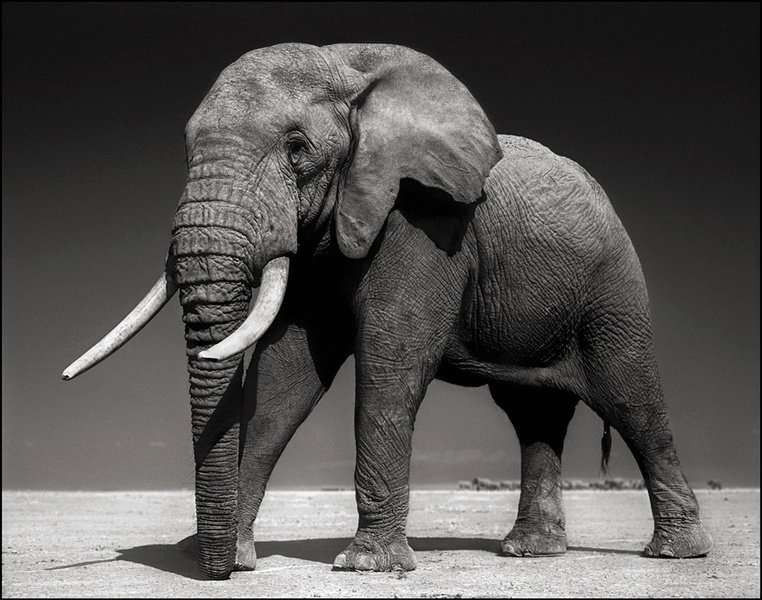

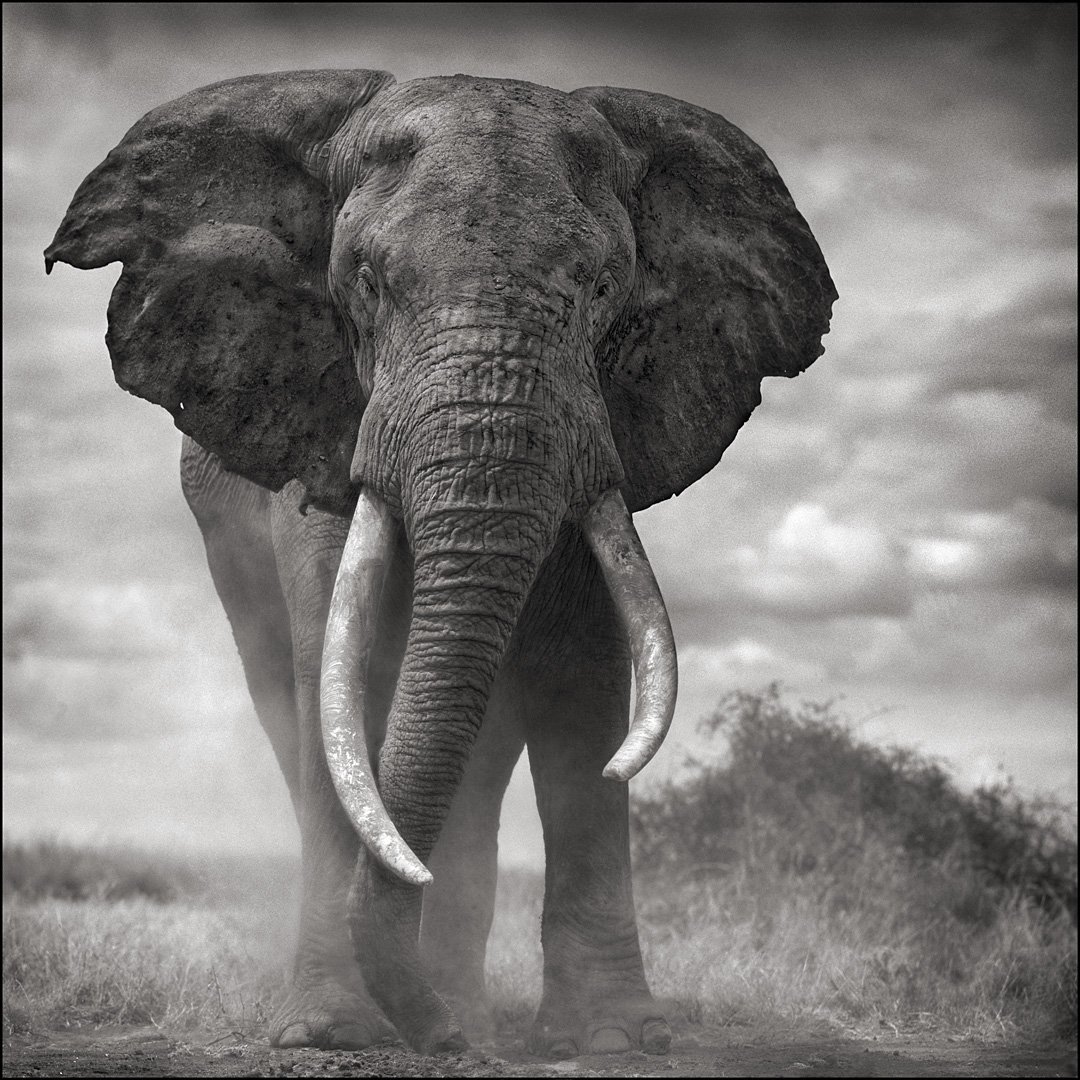

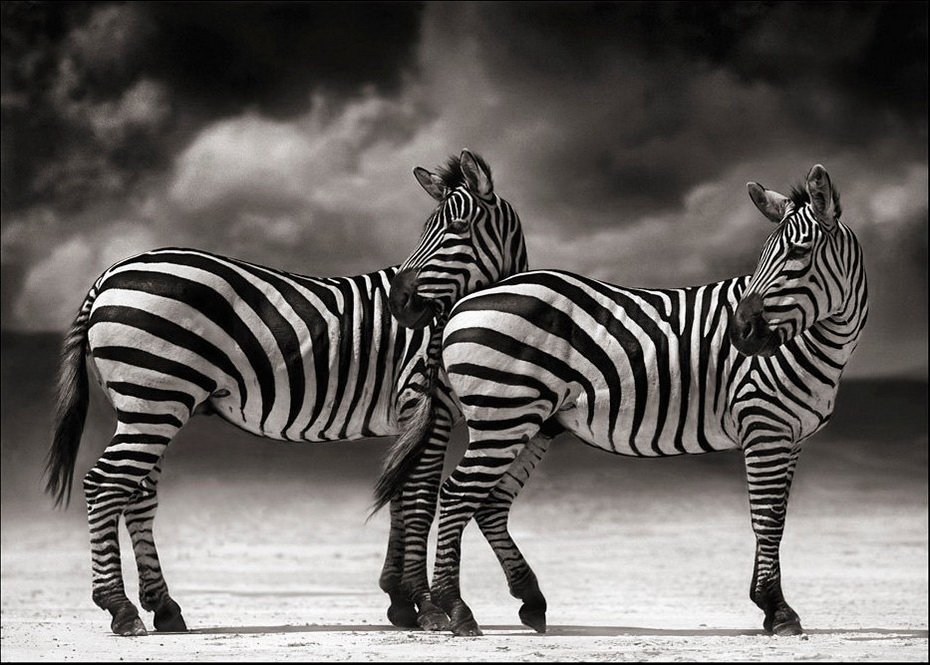

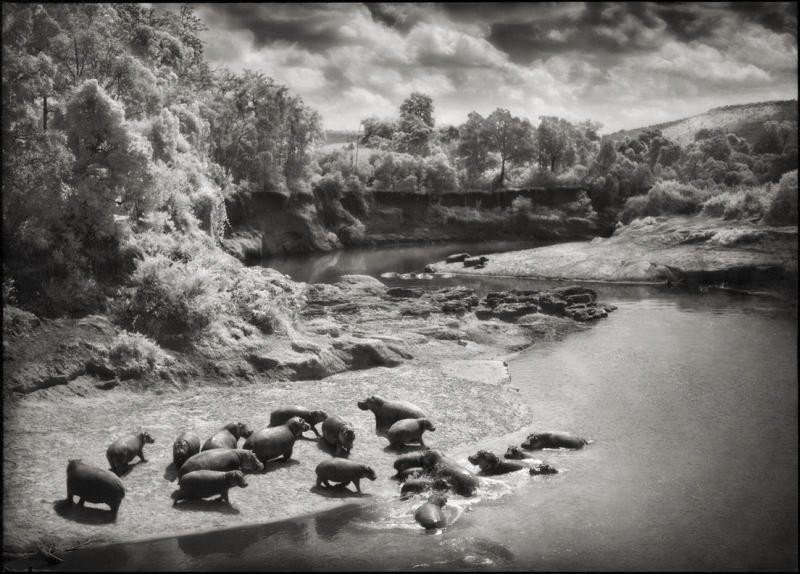

When “On this Earth” landed in 2005, being the first part of Nick Brandt‘s astounding trilogy dedicated to the wondrous yet vanishing African wildlife, it took the public by storm. Featuring 66 images photographed between 2000 and 2004, Brandt’s work breaks most established norms in animal photography. Distancing himself from conventional wildlife photographers, Nick Brandt’s images capture the primordial and untainted essence of the animals depicted. Endless pristine landscapes, void of any human presence, and huge skies form the canvas for the animal portraits Brandt paints with light. His unusual subjects pose for him calmly, as if they were visitors to a master portraitist’s studio.

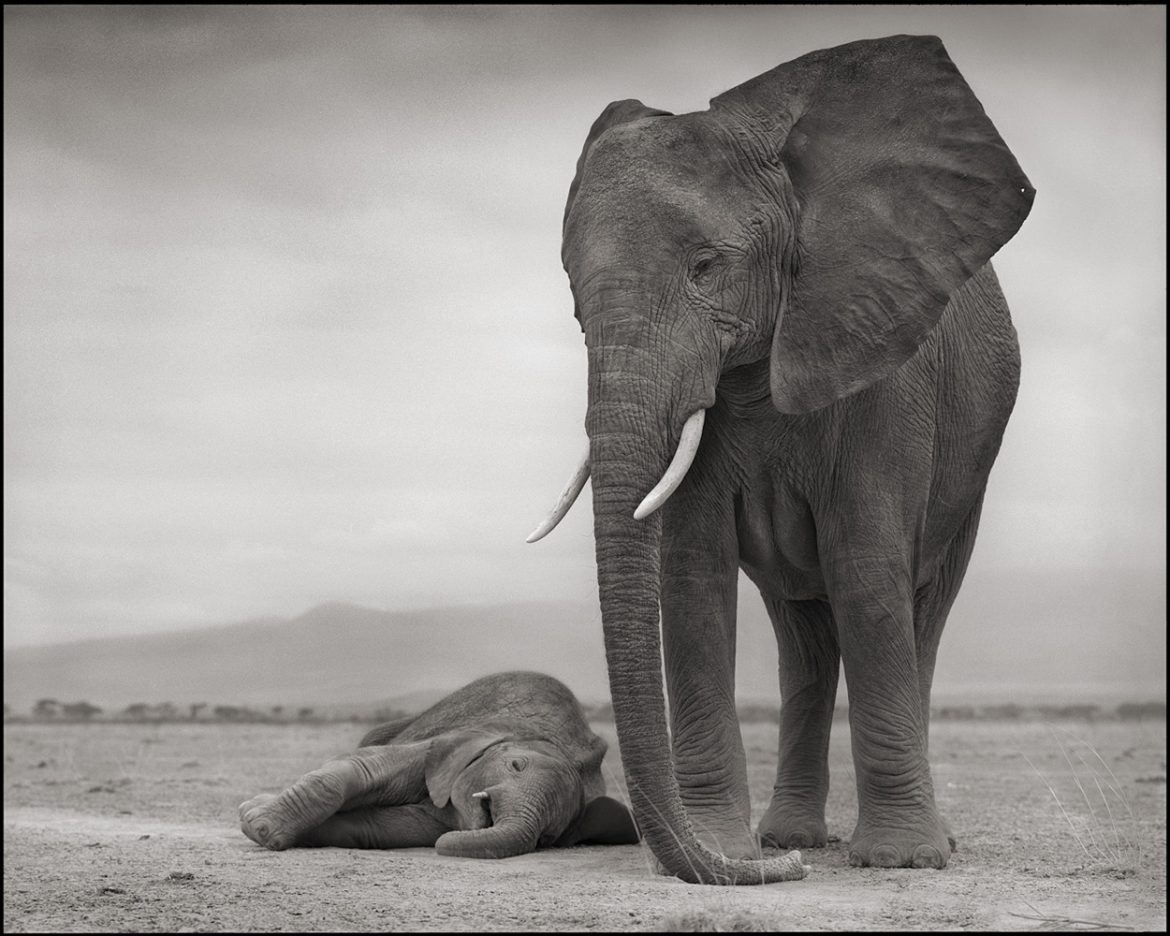

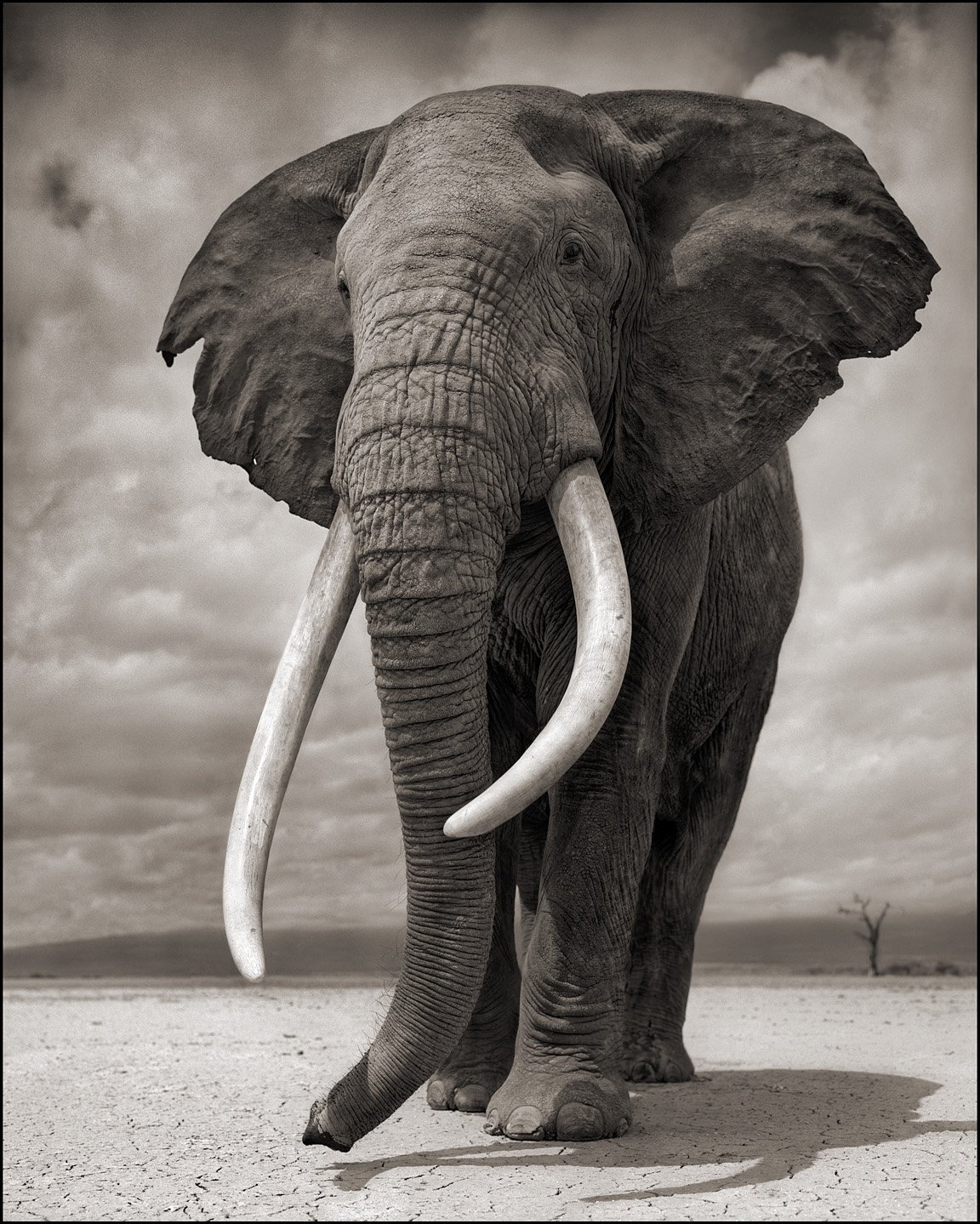

The next two installments, “A Shadow Falls”, 2009, and “Across the Ravaged Land”, 2013, act as the public’s visual guide through the catastrophe that takes place in the Dark Continent’s vast expanses of land, foretelling the impeding doom. The beauty of the first tome’s images, becomes a profound melancholy enshrouding the second one, preparing us for of the impact of loss and decay seen in the third and last book. Green pastures teeming with animal activity, slowly turn to barren still landscapes, empty of animals; bones and parched earth are the sole remains of a better era. Humans make their presence known for the first time in the last book, mankind being a catalyst to the survival or demise of ecosystems.

The titles of the books form a phrase that perfectly describes the loss of Eden of the first tome to the grim and brutal realities of the last, “On this Earth, a Shadow Falls, Across the Ravaged Land”.

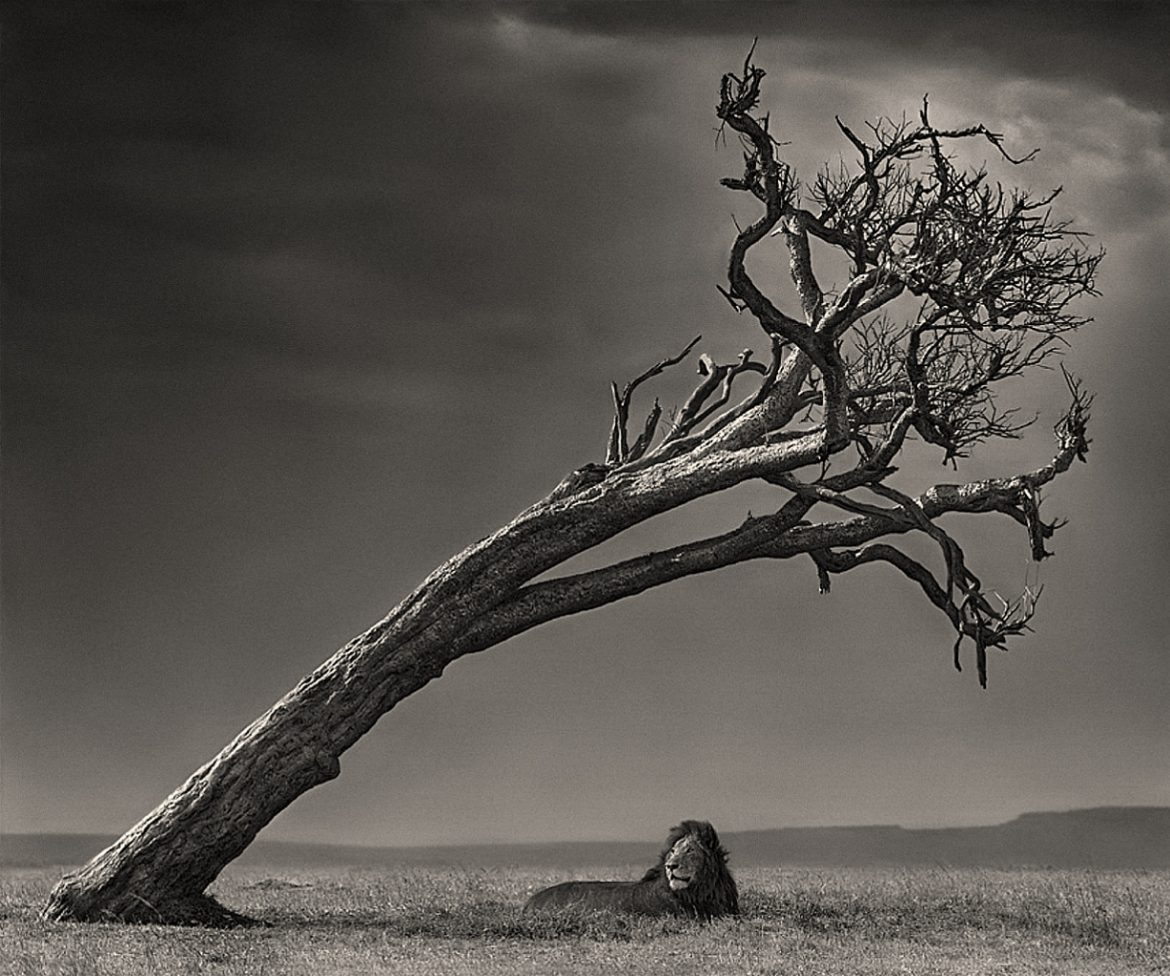

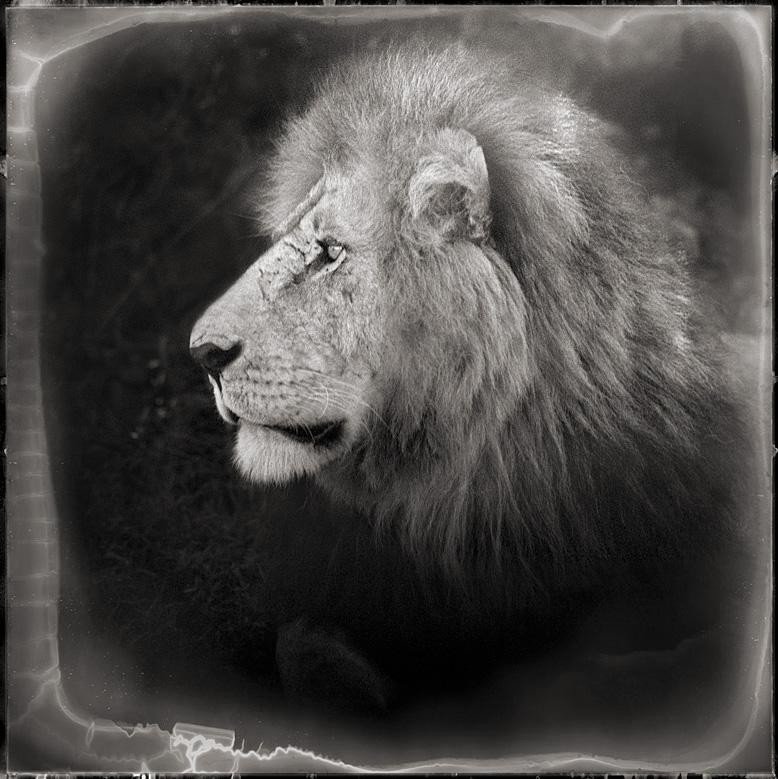

Unlike wildlife photographers, Brandt does not go after action and drama; you will not find hyenas eating carrion or lionesses hunting prey, nature’s cycle of life and death is hinted. Through his lens, animals cease being animals in the usual perceived manner of documentary photography; unveiling their souls, they trust us with elements that we humans consider our own species’ unique property, they speak to us. What is more, Brandt denies himself the use of telefocus lenses, as he explains: “You wouldn’t take a portrait of a human being from a hundred feet away and expect to capture their spirit; you’d move in close.” Brandt has to be armed with patience in order to immortalise what he seeks; the animals’ state of being. In the era of megapixels, zoom lenses and autofocus, it is surprising how impractical the way he works is. Opting to shoot with normal lenses and his, slow to use, analogue camera (a Pentax 6×7), ten images per roll of film and lack of any automation in light metering or focusing make up for a daunting task. His technique, akin to early 20th cent portrait photography, has been the subject of many debates, whether they are products of digital editing or achieved in camera. Brandt himself remains cryptic to his method, denying any digital editing to achieve the coveted shallow depth of field his images prominently feature. However, he has disclosed that all tonal enhancements have been done digitally after scanning the negative. The internet is full of futile attempts to imitate his look.

All started with Nick Brand’ts visit to Tanzania in 1995 to direct the video for Michael Jackson’s “Earth song”.

The sheer beauty of East Africa’s iconic nature captivated the Londoner, at the time living and working in the US as a director, who decided to realise these feeling into images not only for art’s sake (his books have fantastic sales and prints command very high prices), but to also educate and inform the public on the continuing disaster happening due to poaching and loss of land in Eastern Africa.

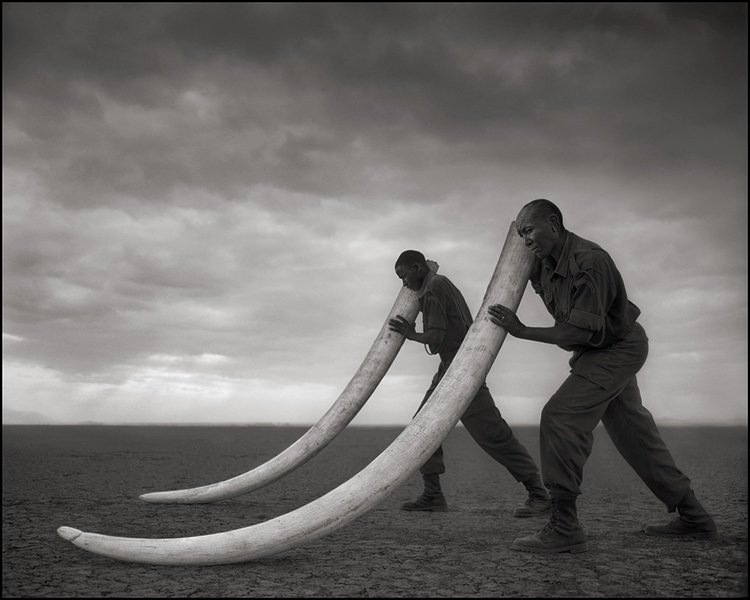

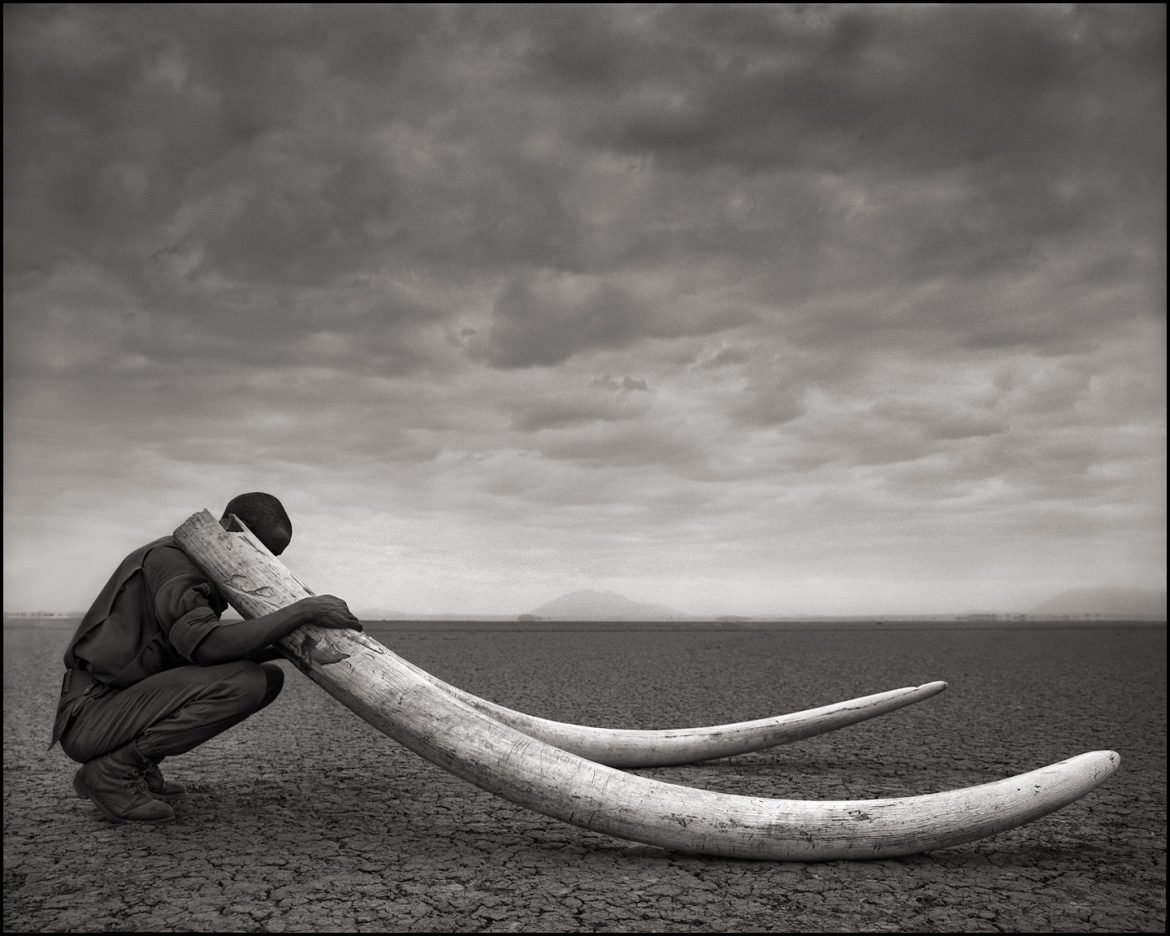

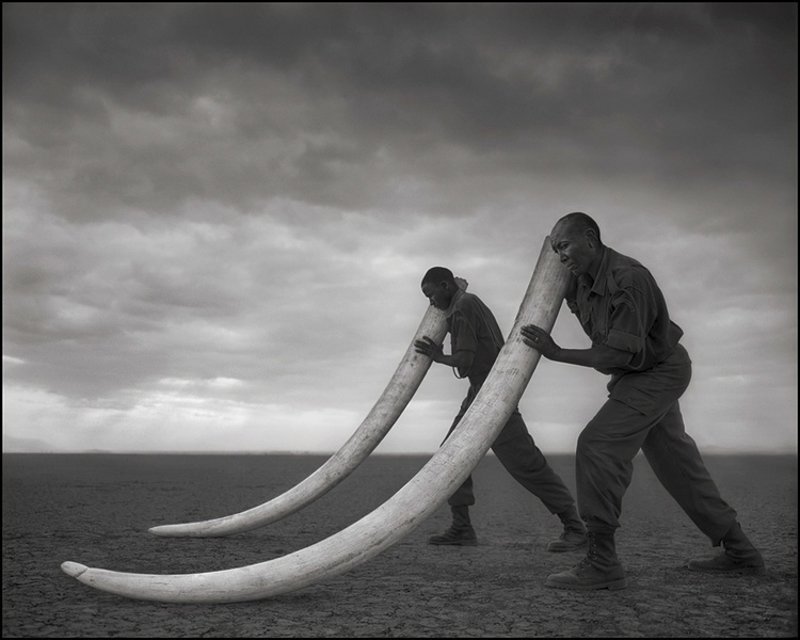

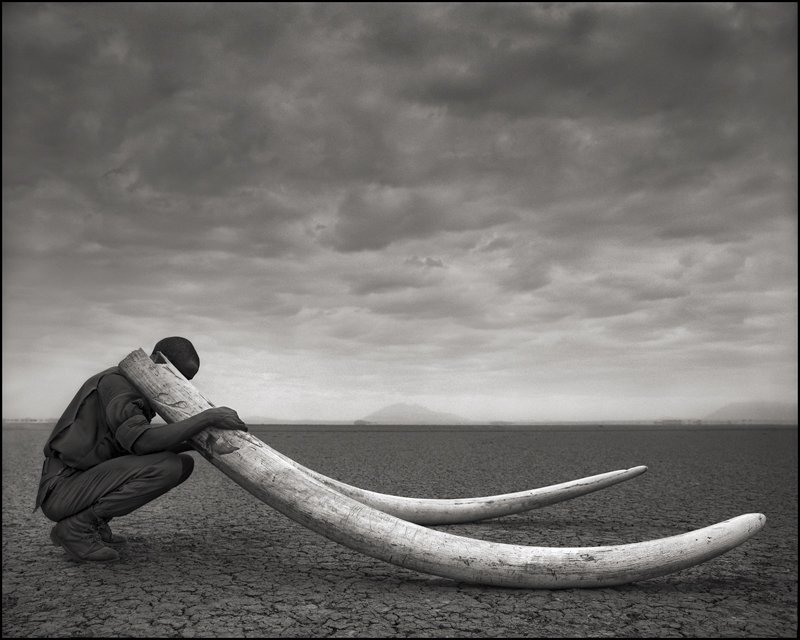

In this regard, Nick Brandt has created, along with conservationist Richard Bonham, the Big Life Foundation, an organisation dedicated to protecting wild animals populations in east Africa. Their body parts are highly sought in the markets of the Far East and poachers, ever after profit, are on the hunt again. 310 local rangers in 31 posts, heroes in their own regard, funded by the foundation have undertook the heraclean task of protecting a 2 million acres (8,100 km2) ecosystem in Kenya and Tanzania, tracking animals and poachers alike. The results speak volumes of Big Life’s efficiency; being the only organisation in East Africa that has achieved what other national foundations could not easily achieve, cross border patrols.

The Rangers depicted here hold tusks of elephants slaughtered by poachers prior to the formation of Big Life. Once again, man is Nature’s worst and cruelest enemy.

“With the lion trophy, for example, I’m hoping to create the feeling that it’s looking across the plains where once it roamed.”

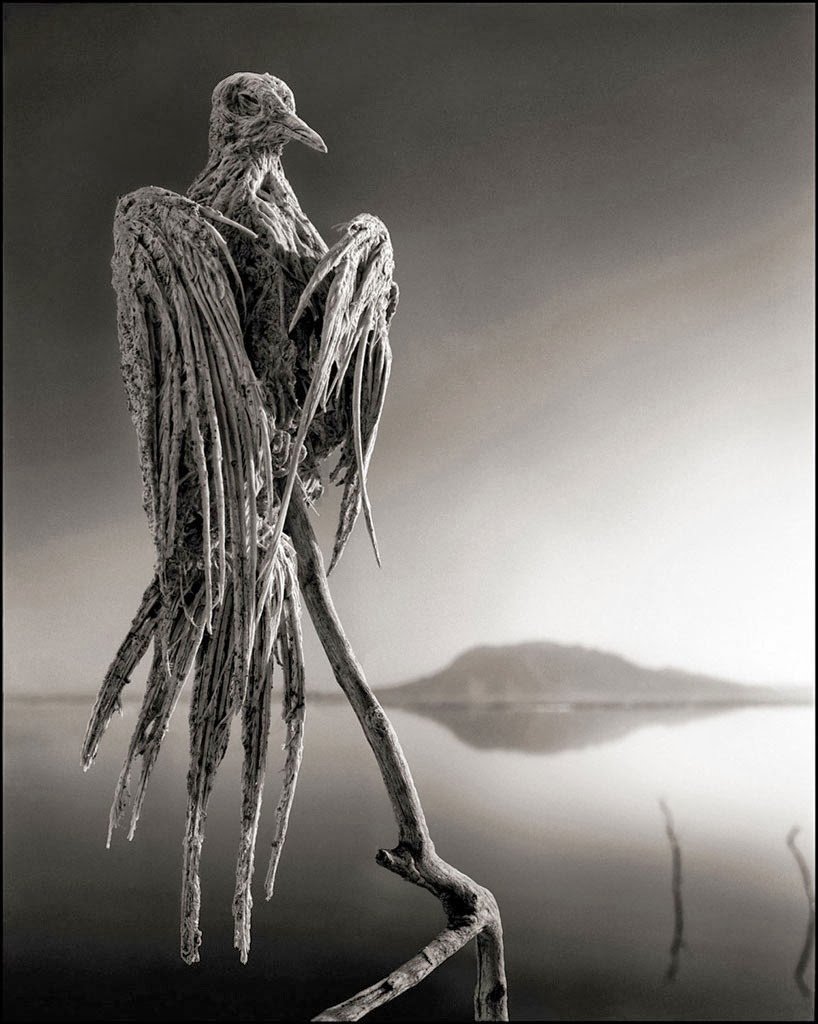

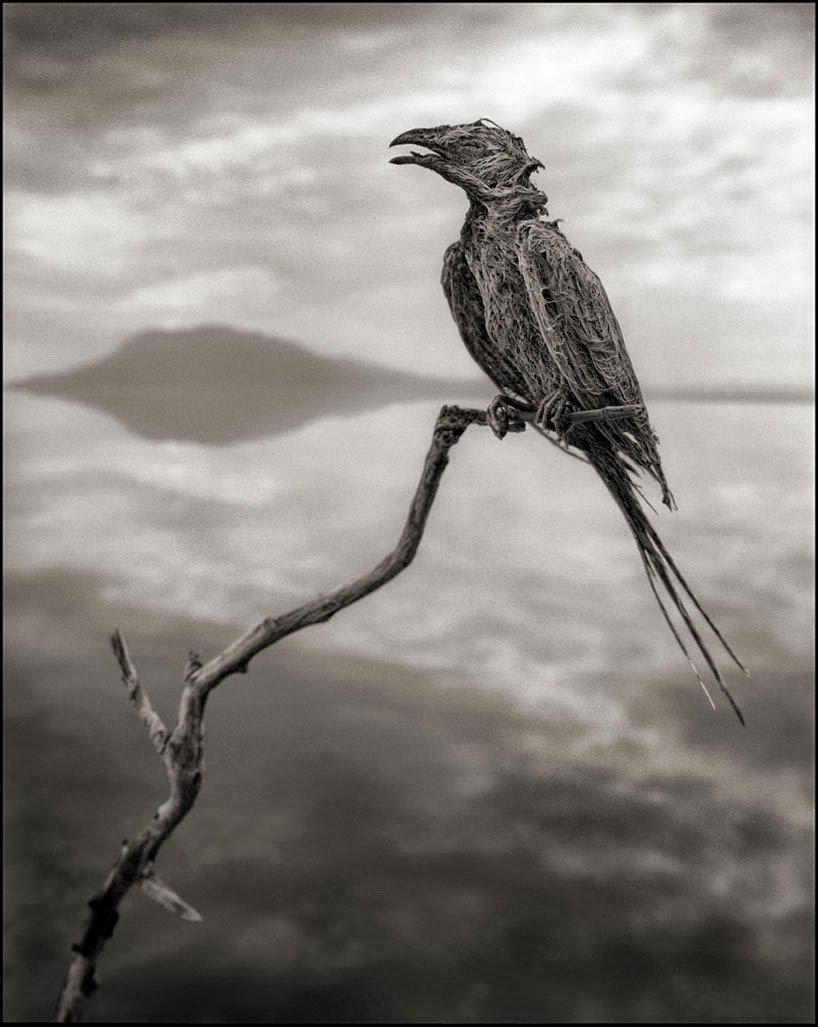

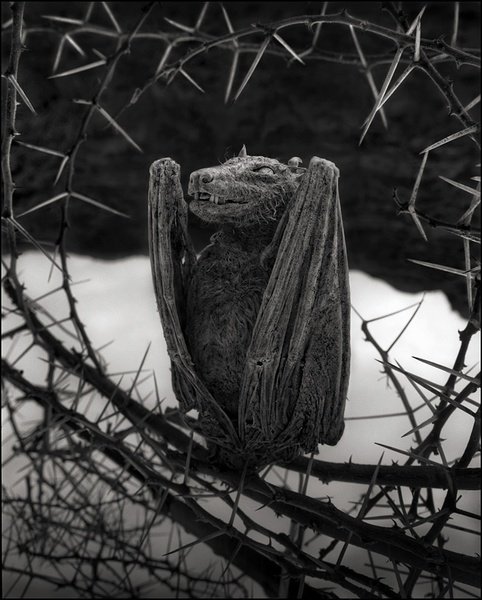

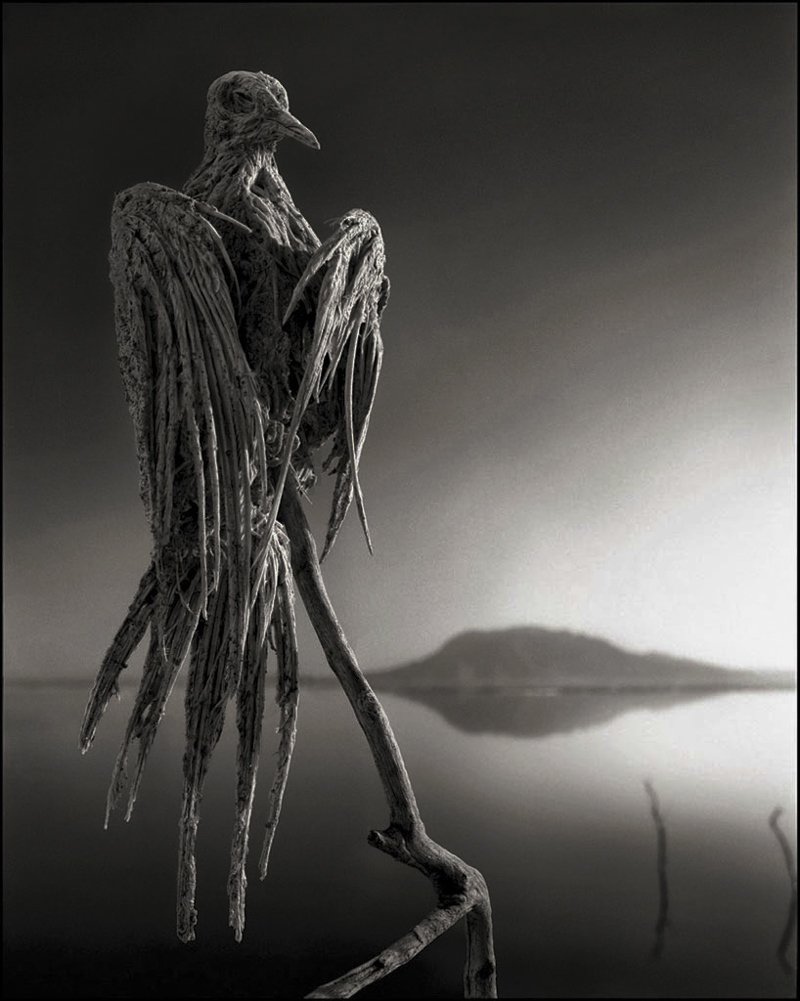

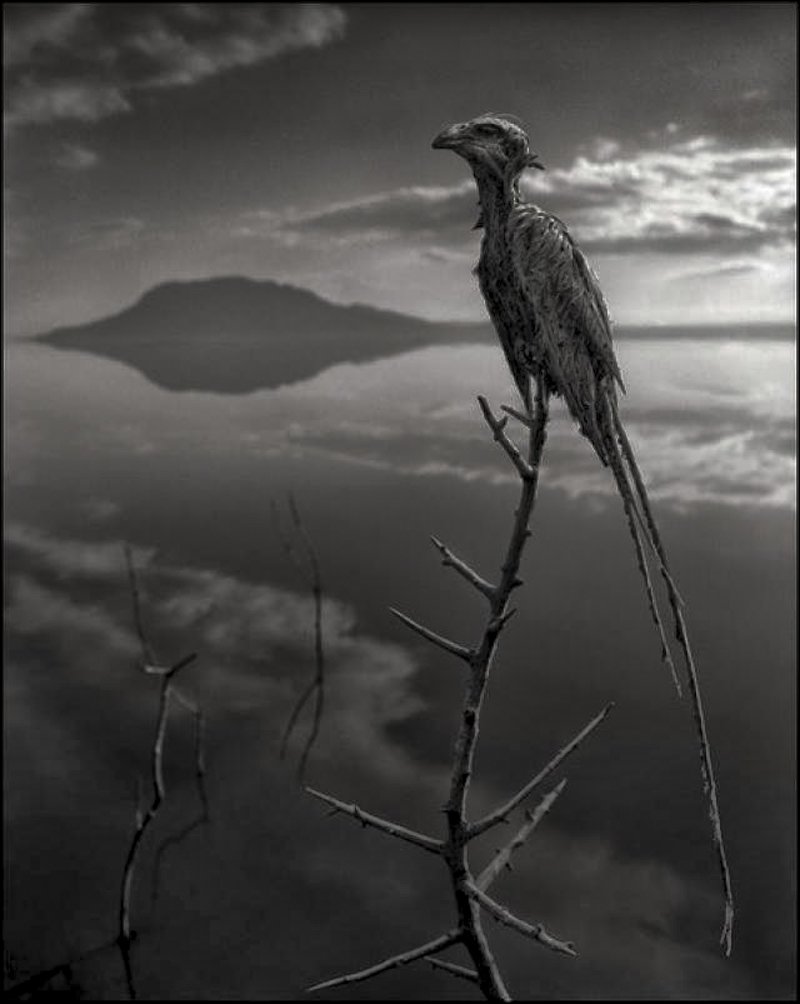

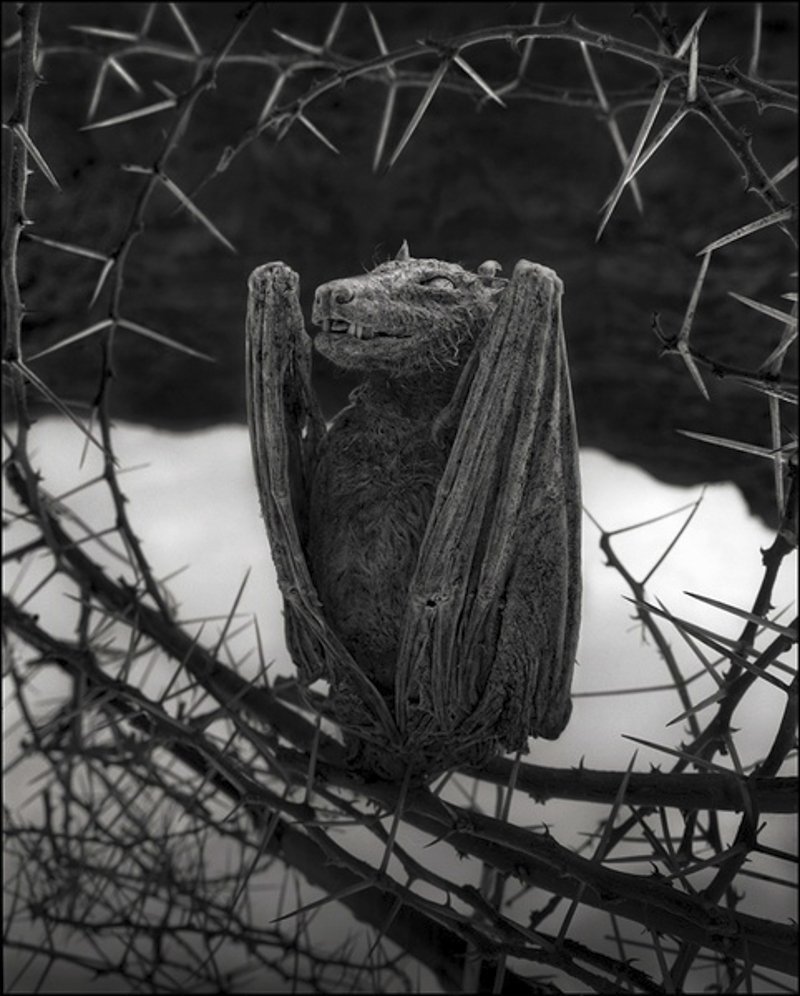

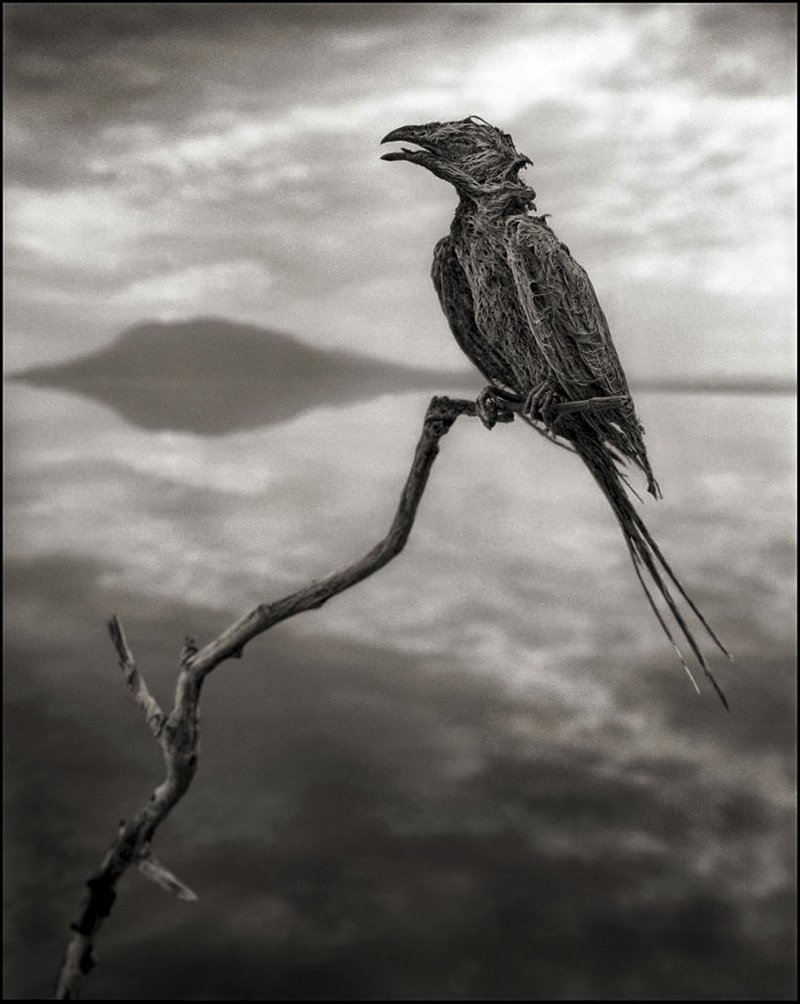

A different addition to “Across the Ravaged Land”, the following set of images shot in Lake Natron, sparked international interest, with media spotlights focusing on this rather unknown, for the many, part of southern Tanzania.

Natron, a very hot and alkaline salt lake, is a nature phenomenon in itself. With temperatures reaching 60 °C (140 °F) and the alkalinity of the water topping at pH of 9 to 10,5, it is as alkaline as ammonia. One would wonder what fauna would inhabit this, well, uninhabitable region, salt loving microorganisms and strange fish aside. The answer to the question would be vast numbers of Lesser Flamingoes and few other species, which in their effort to avoid predators settle around the caustic environment of the lake in order to breed. Predators avoid the area and the “refugees” can freely feed upon spirulina that grows. The haunting images Brandt produced are proof of nature’s mysterious ways. The dead animals have been calcified and preserved and as if out of a sci-fi film, these remains are “directed” by Brandt to take life-like poses for one last time. The inanimate and dead animals, suddenly become otherworldly creatures, inhabitants of a barren ghoulish world.

What the future holds in store, no one can tell. If the efforts of Big Life and other similar NGOs in Africa will help preserve the necessary living space, under constant threat of human “development”, or not, remains to be seen.

According to Brandt : “The only hope for conservation in most of Africa is a collaboration with the local communities. They understand that without the wildlife they have no long-term economic future so it’s a case of the conservation supporting the people and then the people will support the conservation. So in pockets there are a few battles being won but across much of the continent, for lack of resources and infrastructure – you need community, wildlife, tourism, government and NGOs all in place, it’s difficult. When you don’t have these things in place the chances are, the battles will be lost”.